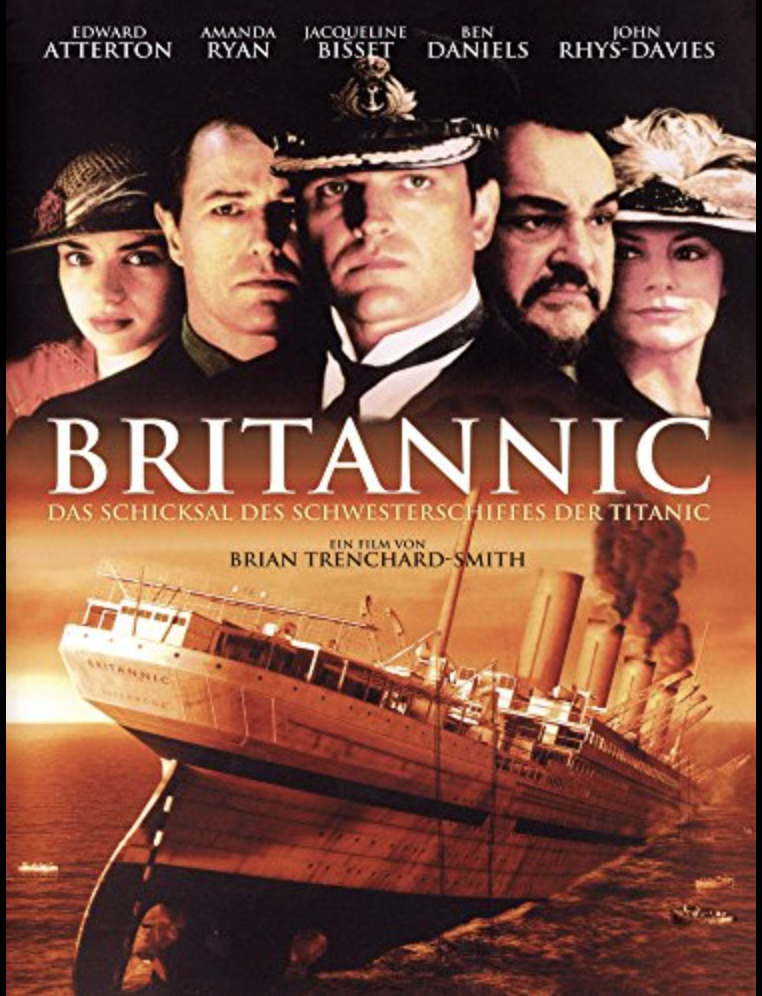

Movie Censorship during my formative years by Brian Trenchard-Smith

(Disclaimer, this post contains images of cinematic nudity and violence within historical context.)

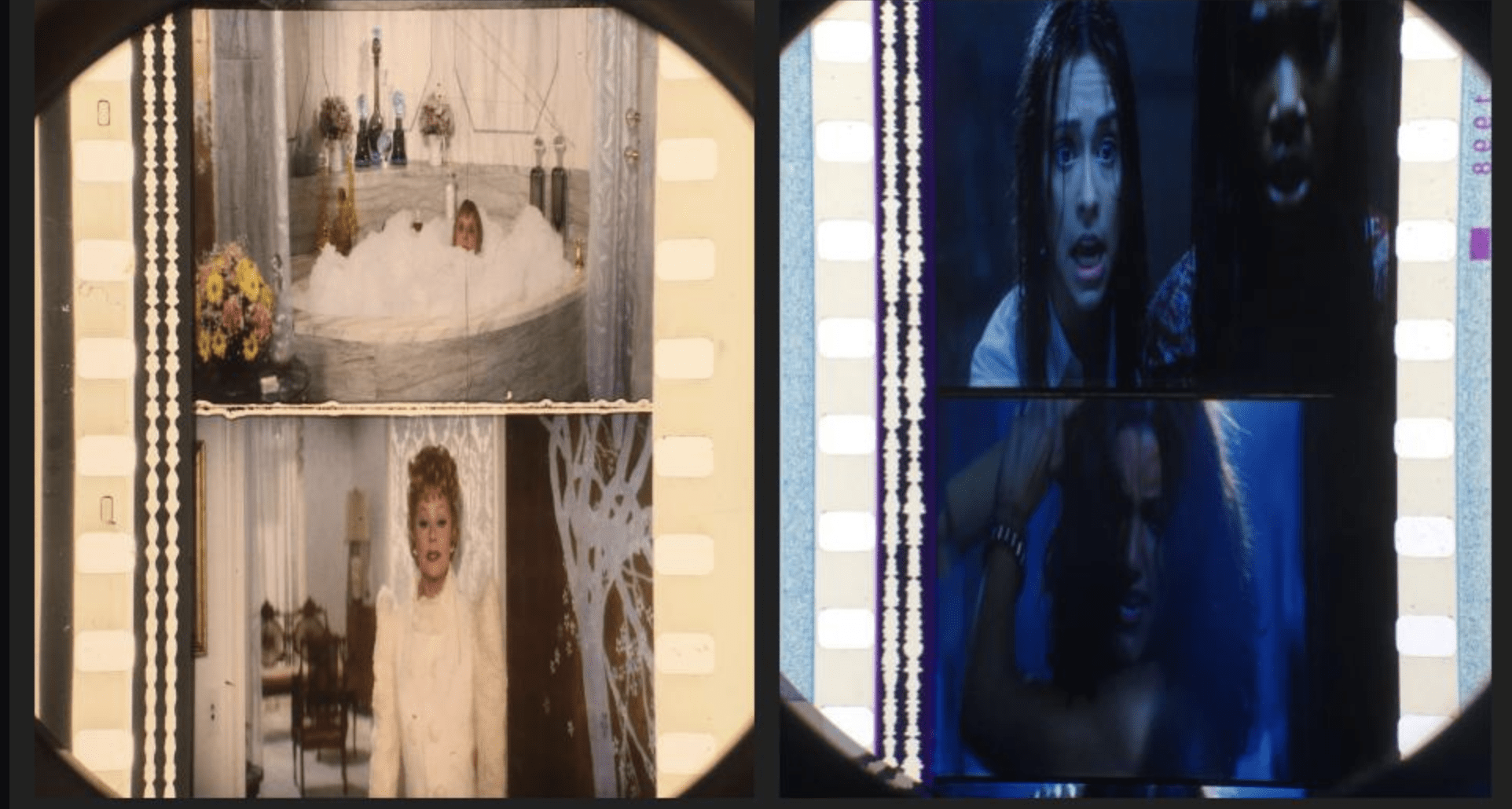

Once Upon A Time in Movies… they were shot on 35MM celluloid. Forgive me if I get into the Cinema weeds here. It’s a love that never dies. The exposed film was processed, work-printed, edited, and the negative matched to the final cut. In the change of images in the left-hand film strip, you can see a slight overlap of cement along the frame line, incurred when the splicer pressed down to glue the outgoing and incoming frames of negative together. What cinema audiences saw was a continuous positive print made from the spliced negative, that absorbed the splices and so ran smoothly through the projector.

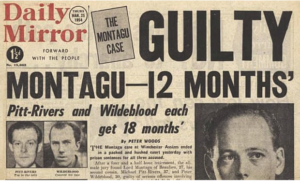

Unless, of course, a CUT was made in the print, where a section had been extracted, then the two ends cemented together. The splice would cause the frame to jump in the projector for a fraction of a second, accompanied by a discordant bump in the soundtrack you see printed beside the sprocket holes, and worse, a disconnect in the flow of the scene. What just happened? Discerning UK audiences of action, Sci-Fi and horror knew that something had been CENSORED!

Why did they cut that bit?

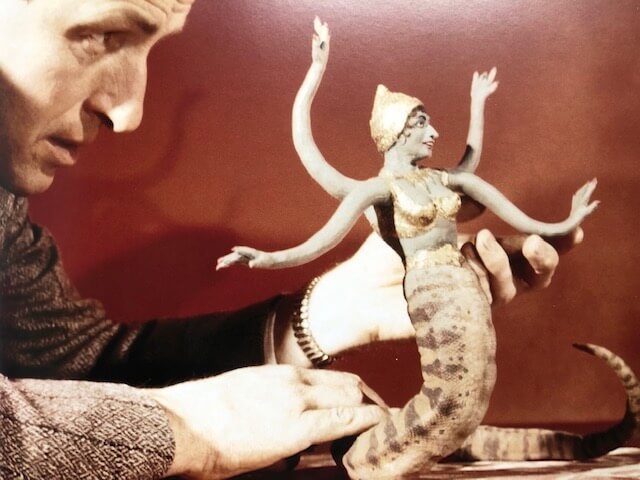

I was 15 when I first encountered this phenomenon during a 1961 splice-ridden re-issue of Ray Harryhausen’s The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, a groundbreaking fantasy adventure that received a hard time from the British Board of Film Censors. The obvious cuts prompted in me a lifelong fascination with the whys and wherefores of movie censorship as an instrument of social control from 1899 to 1968 when proscriptive cuts and bans were replaced in the UK & USA with classification by age. Let’s start with the origin of my interest The 7th Voyage of Sinbad as an example of the BBFC’s attitude to violence and horror in the 1950’s.

Reel 1:

Remove the four close-ups of snake-tailed woman being strangled by her own tail.

Reel 3:

Reel 3:

Remove close shots of Cyclops gloating over man on spit.

According to Ray Harryhausen, the Cyclops is licking his lips at the prospect of the meal ahead. RHH complained in his book that the British Censor had eliminated a wry moment that humanized the Cyclops.

Remove close shot of Cyclops’ face as it peers into cave before being blinded.

I wondered “why was this shot deleted?” Was the monster’s deformity too horrific at such proximity? It is the closest shot yet of the Cyclops’ single eye, placed to highlight the target of the blazing firebrand that Kerwin Matthews launches in the next shot. It invites the audience to imagine the imminent damage to the eyeball. In fact, the eye poke takes place off screen, and the wound is never seen. The British Board of Film Censors’ philosophy was that children under sixteen years of age were impressionable and emotionally fragile. They should be protected from nightmarish images, which could warp their development.. Further cuts were required, otherwise The 7th Voyage of Sinbad would be given an ‘X’ Certificate, under sixteens not admitted, with significant box office consequences. Many provincial “family cinemas” in the UK of 1958 would not play ‘X’ Certificate films. No Hammer Horrors in our parish, thank you very much. Columbia could not afford to restrict the British release of a movie that had been a sleeper hit in the US the previous year. The cuts were made to obtain the less punitive ‘A ‘Certificate, which allowed admission to under sixteens, if accompanied by parent or guardian.

Then in 1961, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, the first version I saw, was cut even further to obtain a ‘U’ Certificate to be double billed with The Three Worlds of Gulliver in a holiday re-issue. The most egregious of the cuts: the groundbreaking fight with the skeleton. Too scary for little kids who can come to ‘U’ Certificate films unaccompanied, ruled the BBFC which saw the film as more horror than fantasy. It took till 1975 when the film was reclassified uncut, and British audiences could finally see Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion fantasy as he originally intended. You can check out the classic duel here.

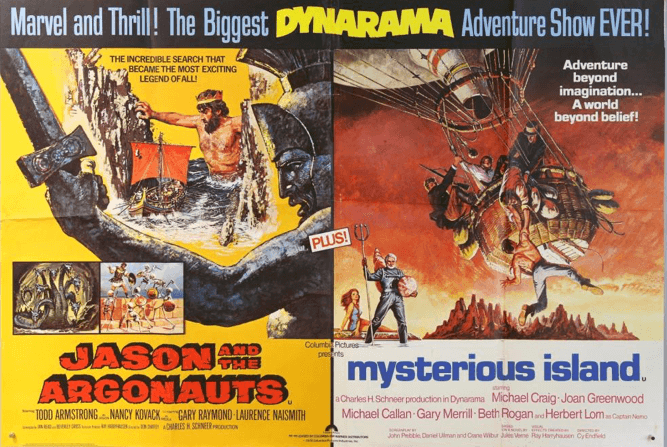

Really? Too disturbing for kids? In a typical censorship anomaly, two years after Sinbad’s truncated re-issue, RHH’s Jason and the Argonauts, with its army of sword swinging skeletons, was passed uncut for a “U” Certificate.

There is much to mock about movie censorship, and I will, but it should be granted that the censors in their own minds were working to protect society from harm. Whether that harm was imaginary continues to be part of the free speech debate, as new technology delivers instant access to toxic material. The debate over free speech is now more contentious than it has ever been. The purpose of this and following essays on the subject is not to fan the flames of the culture wars. It is to put censorship into the context of social history, because censorship reflects its times. What follows is a quick sketch of the origins, intentions, and practice of film censorship, viewed through my personal perspective. I’ll focus mainly on British and American censorship, with comparative examples from Europe and Asia.

ORIGINS

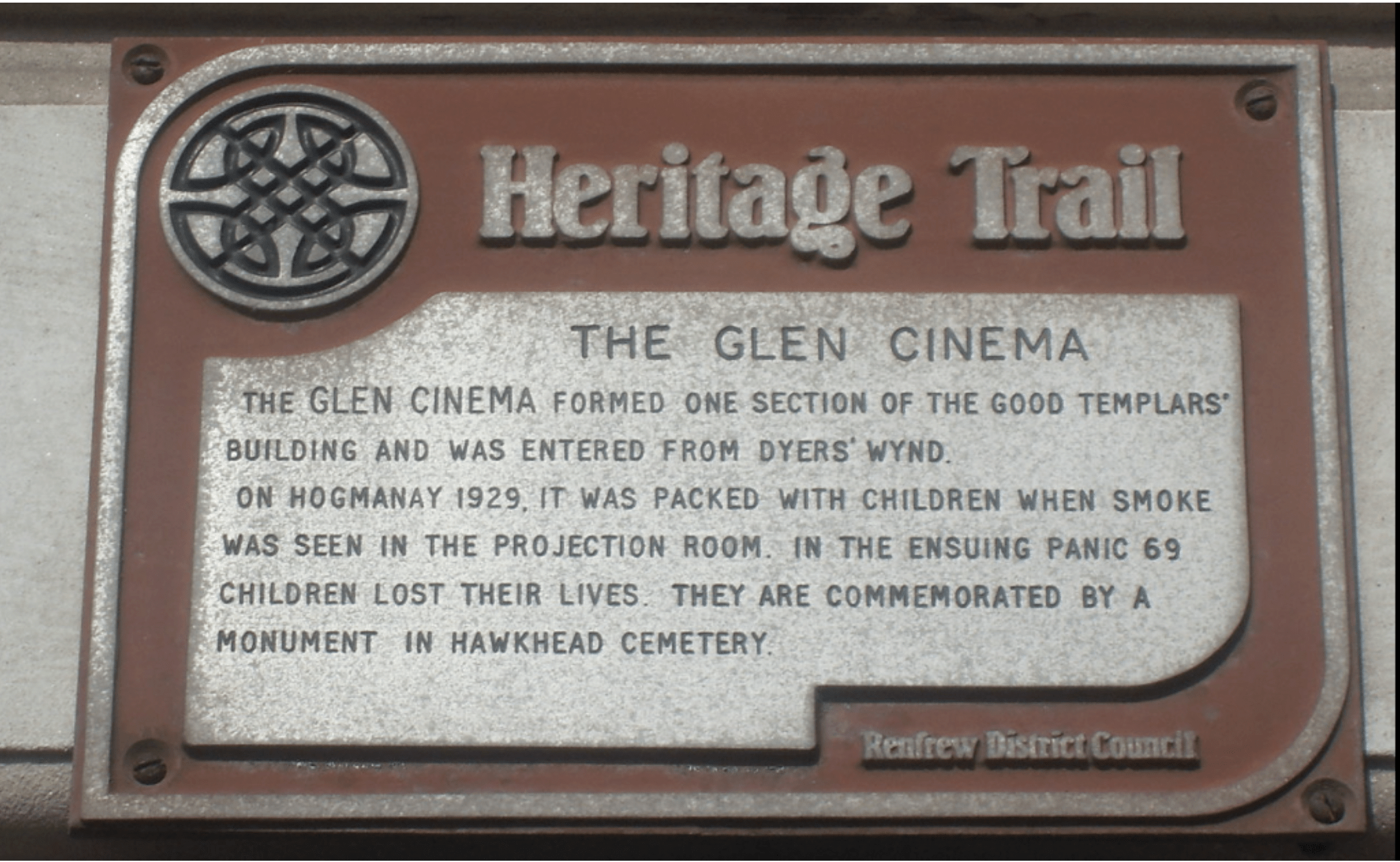

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the new entertainment medium of motion pictures exploded in the tastebuds of an eager public, a visual gelato for a nickel an hour to take them away from the pressures of their lives. The first cinemas were little more than converted storefronts; a screen or a sheet tacked to the wall at one end and a projector at the other, with scattered seats in between and no toilets. There were reports that some patrons became so transfixed by the projected images that they remained in their seats and relieved themselves on the floor, rather than go out to a public toilet. Often there was only one exit, which exacerbated another potential health hazard. 35 MM film was made of cellulose nitrate, which was highly inflammable. If the film jammed in the projector gate, the heat from the projector’s beam could cause it to catch fire within seconds and burn for hours. In 1897 a nitrate fire at a Paris venue killed 140 patrons.

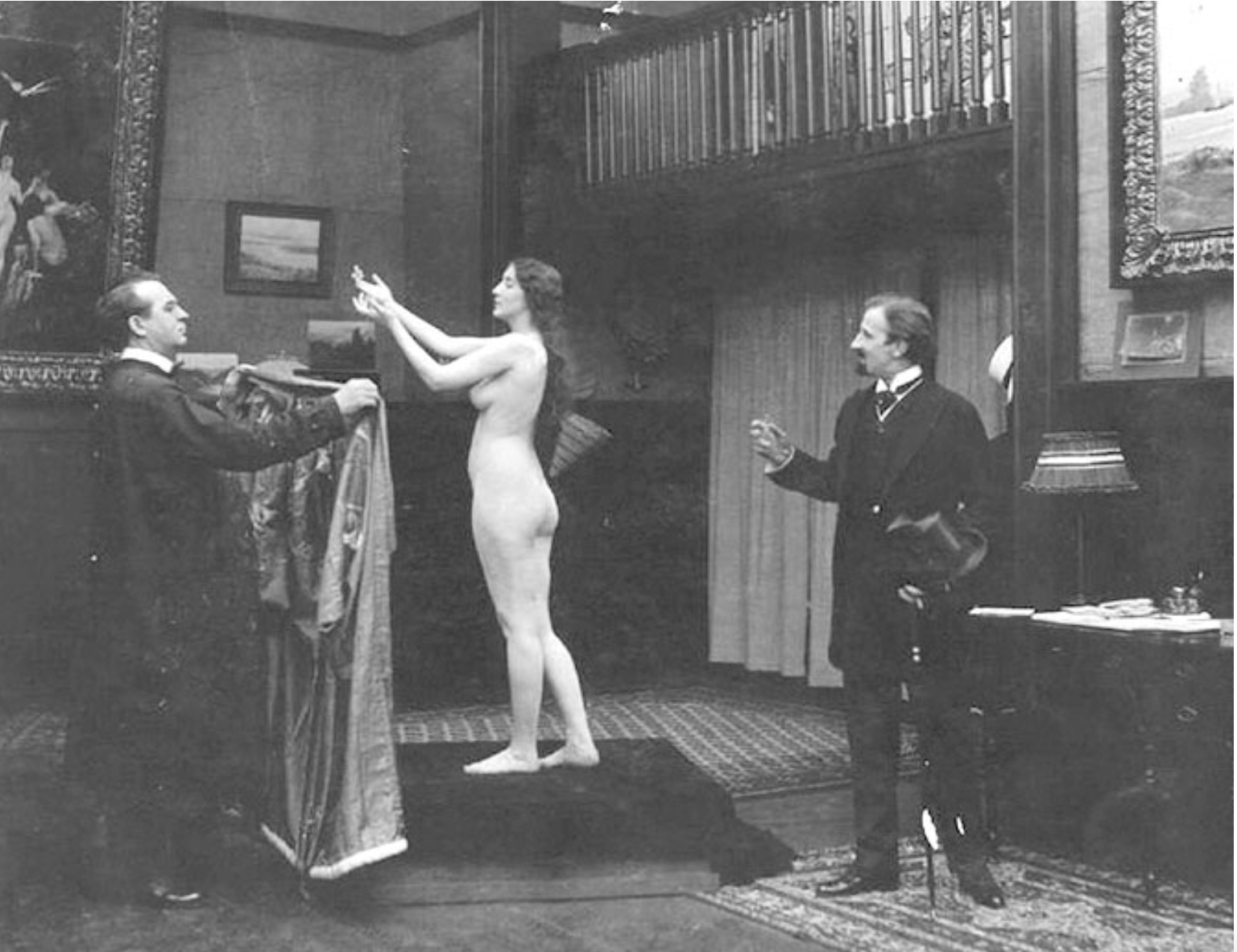

To prevent cinema fires, the London County Council (LCC), exercised its licensing authority over “halls of public entertainment” requiring that projectors be housed in a fireproof box. Local authorities across England and America followed suit. Initially, the motivation for regulating these penny gaffs (UK) or nickelodeons (USA) by local councils was motivated by public safety. A worthy cause, followed inevitably by mission creep. Concerns rose about the content that flickered on their screens. There had always been government censorship or modification of literature and theater. To the middle-class forces of social control, the new medium was working class, consisting mostly of sensationalist entertainment. It was, in their view, commercialized voyeurism and needed supervision.

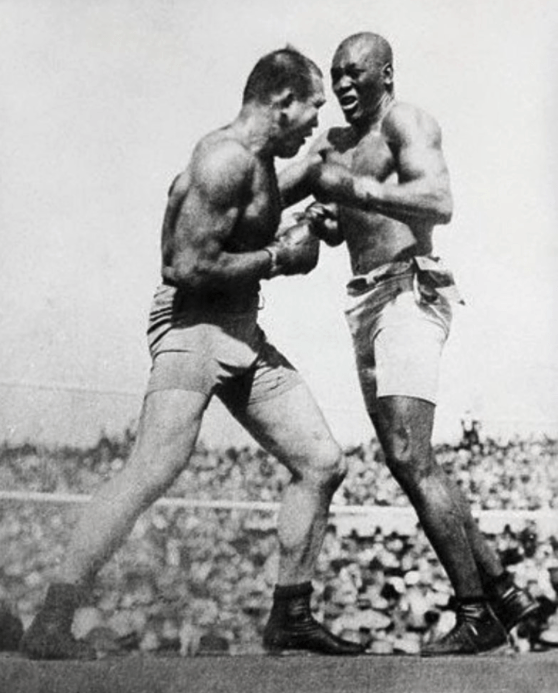

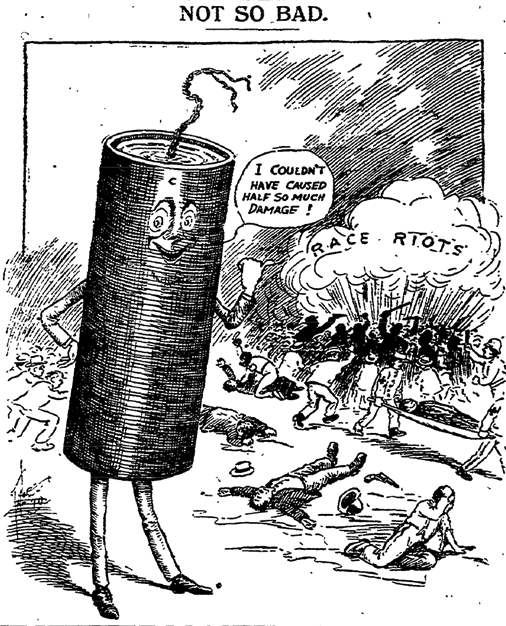

In 1910 the LCC banned a newsreel of the boxing match between heavyweight champion Jack Johnson, a black man, and former champion James Jefferies, dubbed “the great white hope’ who came out of retirement to reclaim the title. His defeat caused race riots across America.

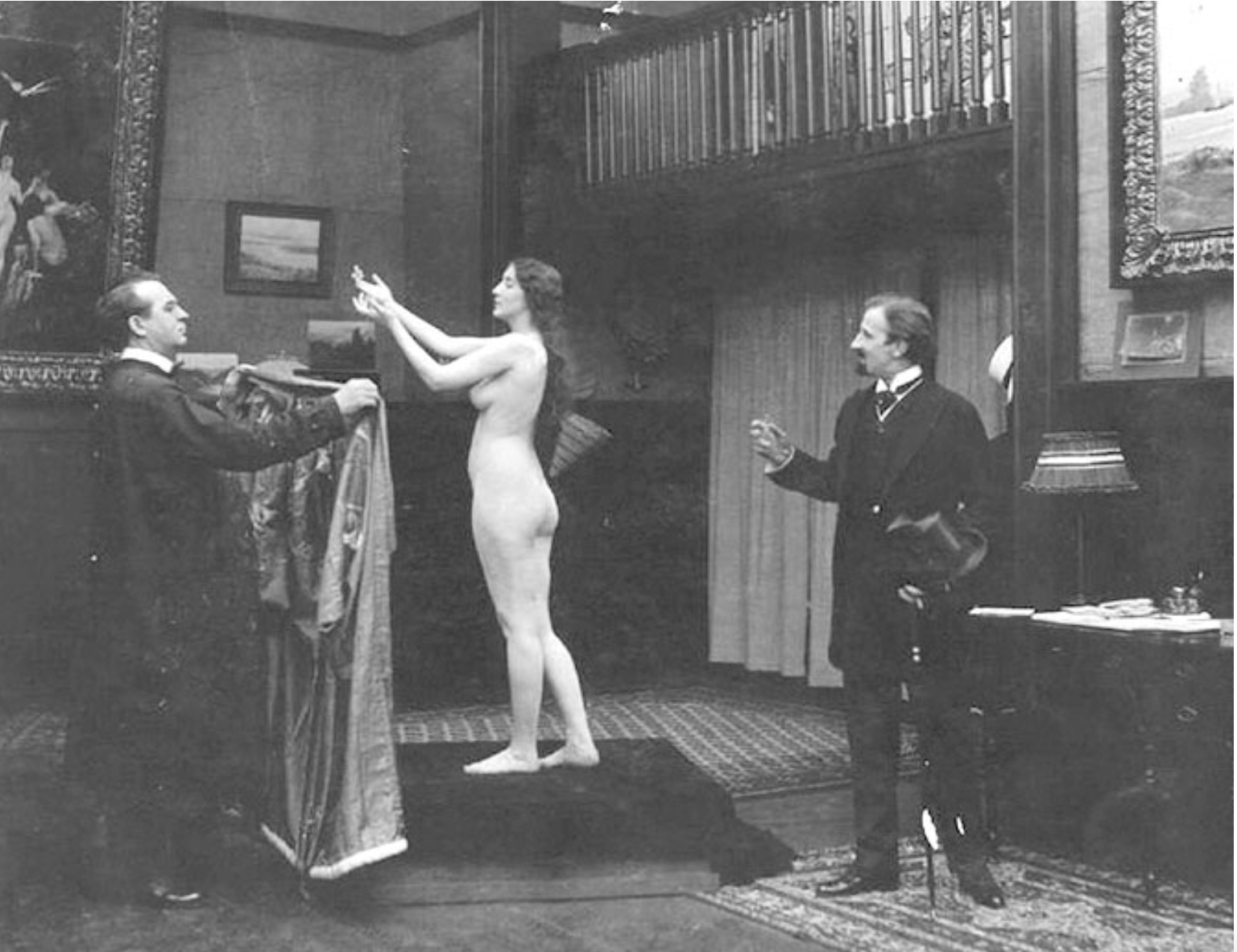

The LA Times rather cavalier cartoon reflected the explosive outcome of Johnson’s victory. Fear of similar violence breaking out in the UK was behind the LCC’s ban. Custodians of public welfare and morality on both sides of the Atlantic regarded the flickers with anxiety and suspicion. Still images of the female form previously confined to solo viewing in arcade peepshows were now in motion on screens in front of scores of people arousing lustful thoughts.

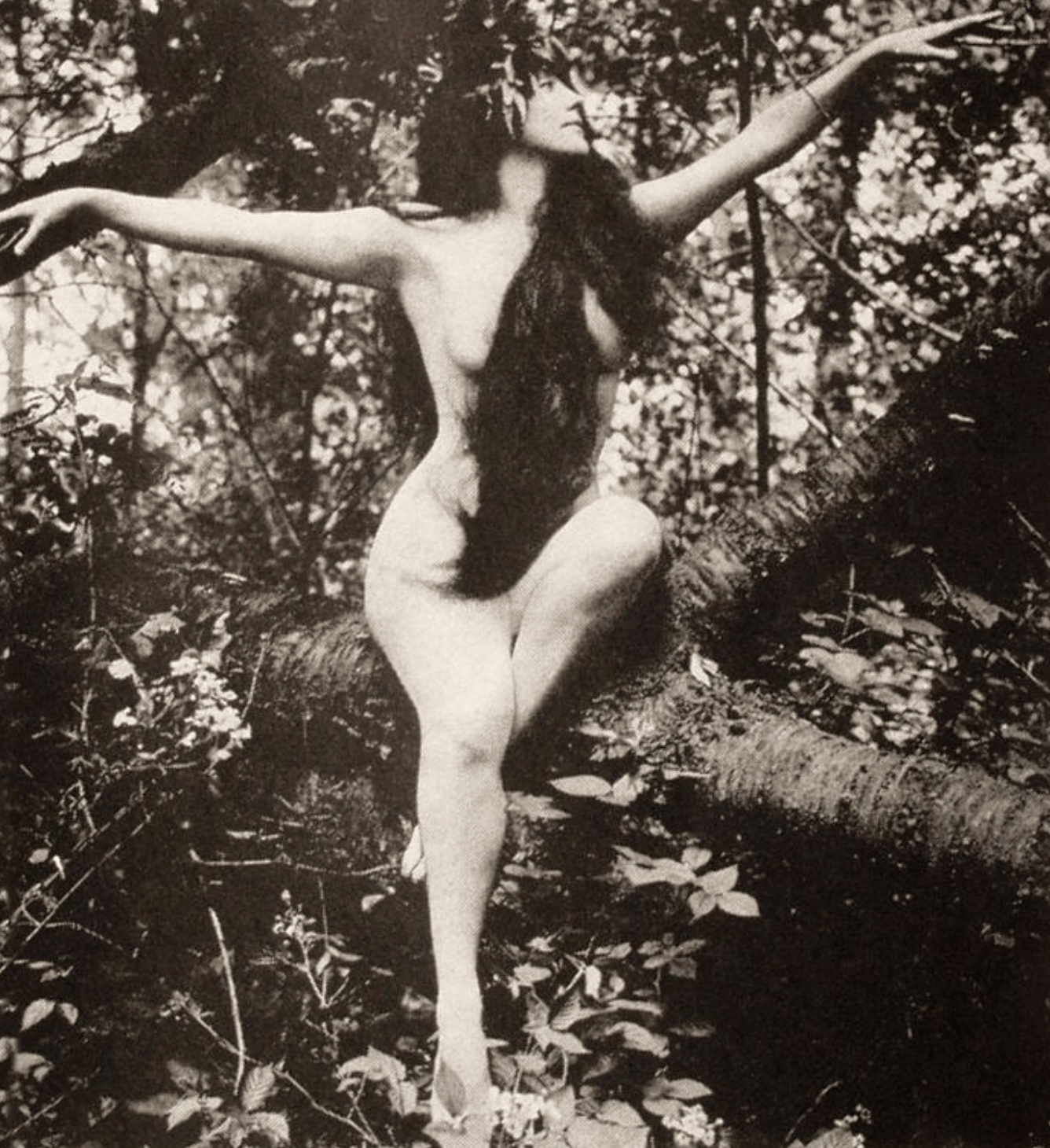

Melies’ After the Ball (1897) is the earliest known film to show nudity, although the model wore a body stocking, and the poured water was faked with black sand.

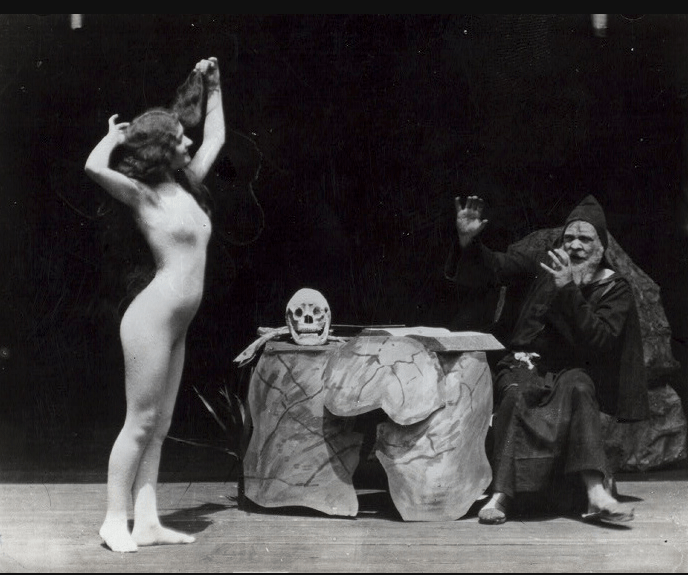

The 1900 Biograph film The Temptation of St. Anthony. depicts female sexuality as a trick of Satan. Such scenes inevitably proved popular, and multiplied. The genie, it seemed, was out of the bottle. Fears arose that cinema would substitute its questionable values for existing mechanisms of socialization. Municipal councils in the UK saw the opportunity to use their licensing power, initially intended for public safety, to become guardians of moral safety by deciding what should or should not be shown in their district; a handy, virtue-signaling platform for the politically ambitious, a way to be seen as on the side of God. Council regulations were added to cinema licenses requiring no films could be shown that were “offensive…improper or indecent”; terms open to wide interpretation.

In which category does this shot of Annette Kellermann from A Daughter of the Gods (1916) fall? Personally, it does an excellent job of emphasizing what it purports to conceal.

This YouTube video, created for the 72 Hour Film Festival in Frederick, Maryland, provides some insight into the self-appointed censors’ preoccupations, foot fetish issues among them. Municipal censorship created confusion for distributors and exhibitors everywhere. Some cuts were required in one county, no cuts in another, different cuts in multiple other counties. rendering distributors unable to standardize their release prints. In America, that often meant that the cuts would never be restored to prints that went on to play in more liberal states, where the cuts were not required. The innovative design of Theda Bara’s bra in the 1917 Cleopatra was denied to many audiences in conservative states.

Bureaucratic anarchy was not good for business. As in the USA, companies in the UK had invested heavily in the nascent motion picture industry. To attract middle class patrons who shunned the penny gaffes, they built picture palaces, with fitted carpets and marble counters for refreshments, serviced by uniformed and courteous staff. Well-appointed cinema chains like Empire, Majestic, and Jewel rapidly attracted the bourgeoisie, doubling their venues each year till in 1911 there were almost 4000 cinemas in England.

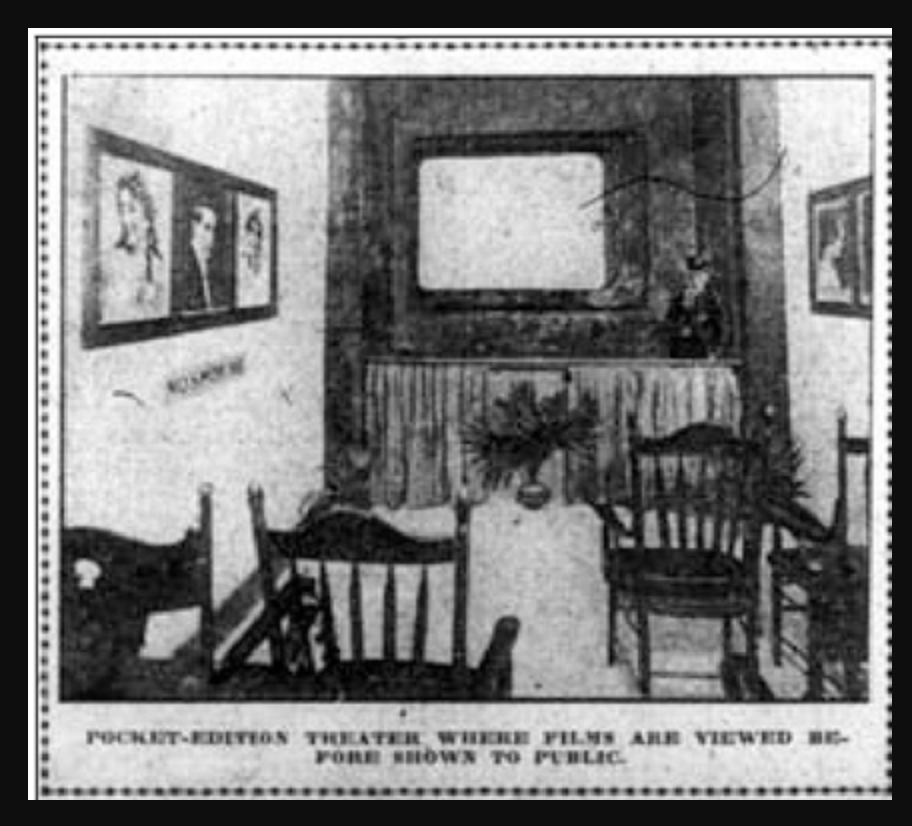

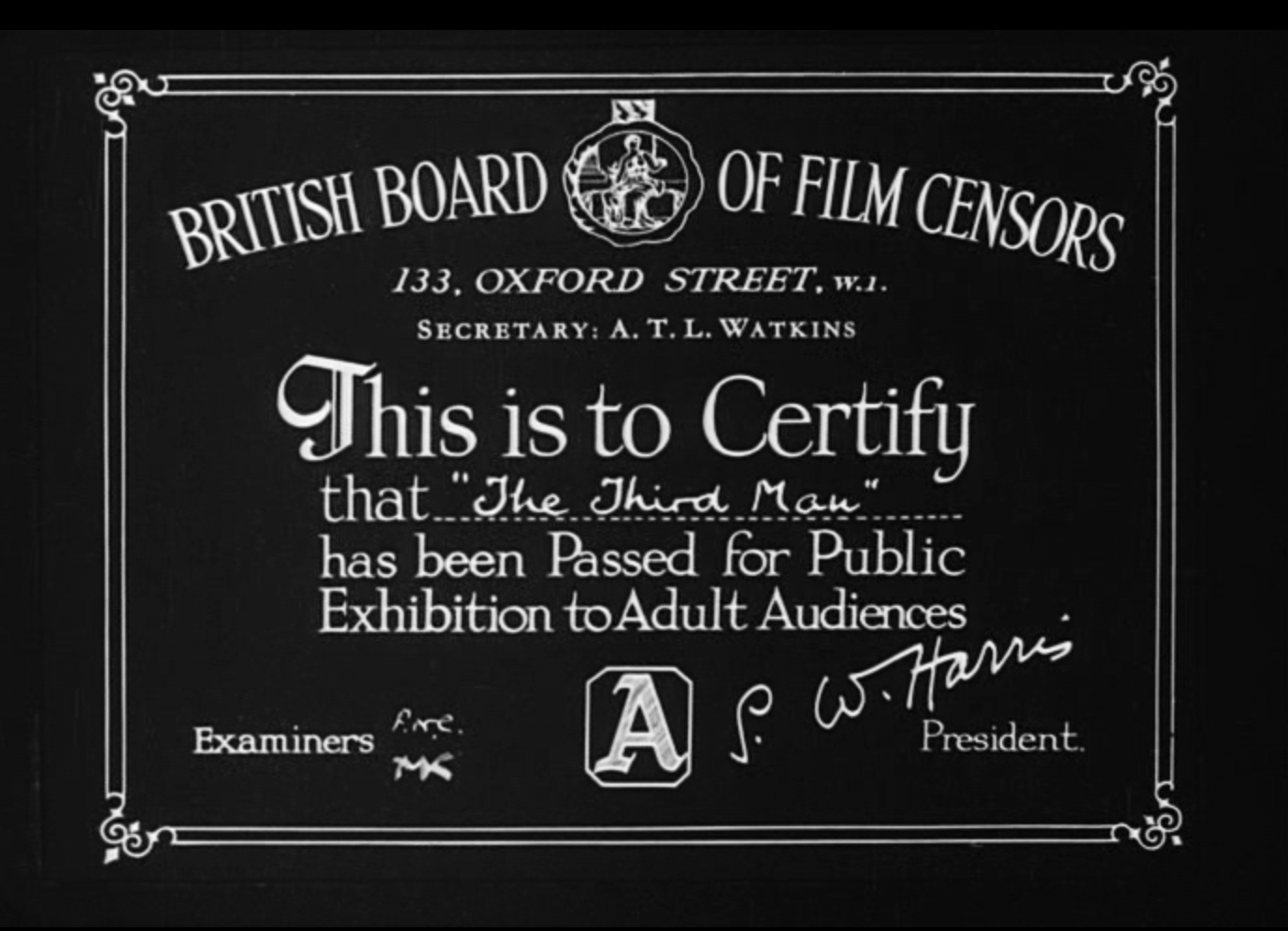

That year the Prime Minister Herbert Asquith “for the first time in his life entered the portals of a cinematograph theater…laughed heartily and continually made witty comments about the pictures.” Cinema going was now respectable, and potentially a gigantic cash cow. Cinema companies invited the government to take over the confused arena of censorship and create common standards that would be accepted by both industry and civic authorities. But the British Home Office was savvy enough to understand that official government censorship would be a political minefield, and preferred to set up a quasi-independent body, working in conjunction with the film industry to take care of the problem at arms-length, providing a level of control without official responsibility. In November 1912, the British House of Commons announced the formation of the British Board of Film Censors. Its President was paid 1000 pounds a year, its four examiners received 300 pounds each. Two films were shown in the viewing room simultaneously in front of all four examiners seated next to each other. Two would be focused on the left screen, two on the right. This practice continued even into the early sound era. Examiners had the power to require cuts, and grant Certificates of Exhibition:

“U” for Universal Exhibition, all ages admitted;

“U” for Universal Exhibition, all ages admitted;

“A”, under sixteens admitted with parent or guardian.

“A”, under sixteens admitted with parent or guardian.

After Frankenstein was released in 1931, a new Certificate was introduced – the “H” (for horror)

This was replaced by the “X” Certificate in 1950. Classifications remained unchanged till 1970.

The official paper certificate granting exhibition was stamped in wax with the BBFC seal.

A display of the censor’s classification became the first image the audience saw before the film began.

The early British censors certainly were productive. In 1913, their first year, they saw 7510 films. Cuts were made in 168. Several were banned outright, citing “indelicate or suggestive situations…indecent dancing…impropriety in conduct and dress.” No sex please, we’re British…

America would not adopt an equivalent classification system for more than 50 years. The American government rejected direct involvement in censorship of movies. They counted on religious pressure groups to force the film industry take care of the problem. It took time but ensured a theocratic underpinning to the eventual American production code. What was most concerning to America’s moral guardians was the motion pictures’ obsession with crime.

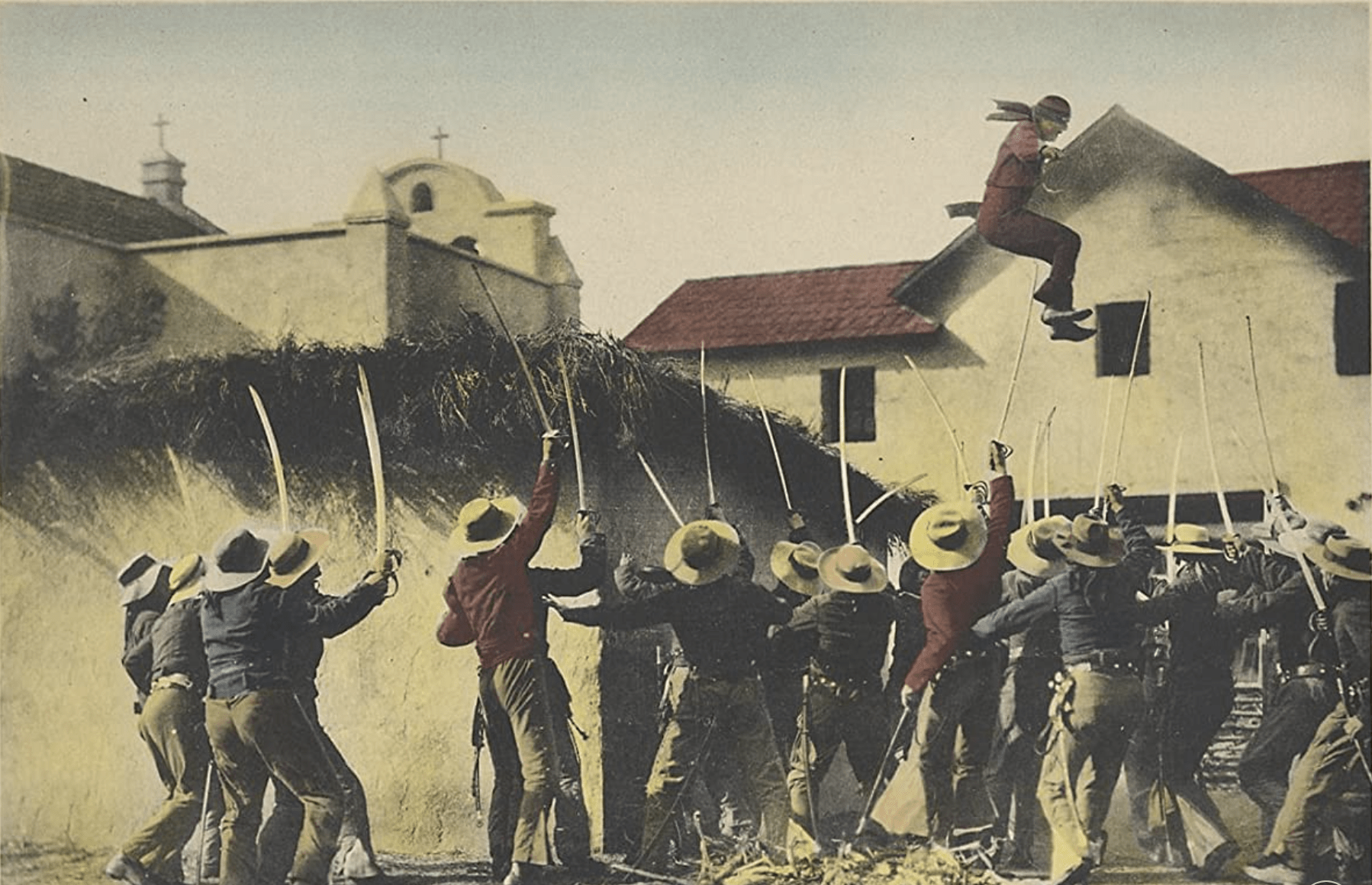

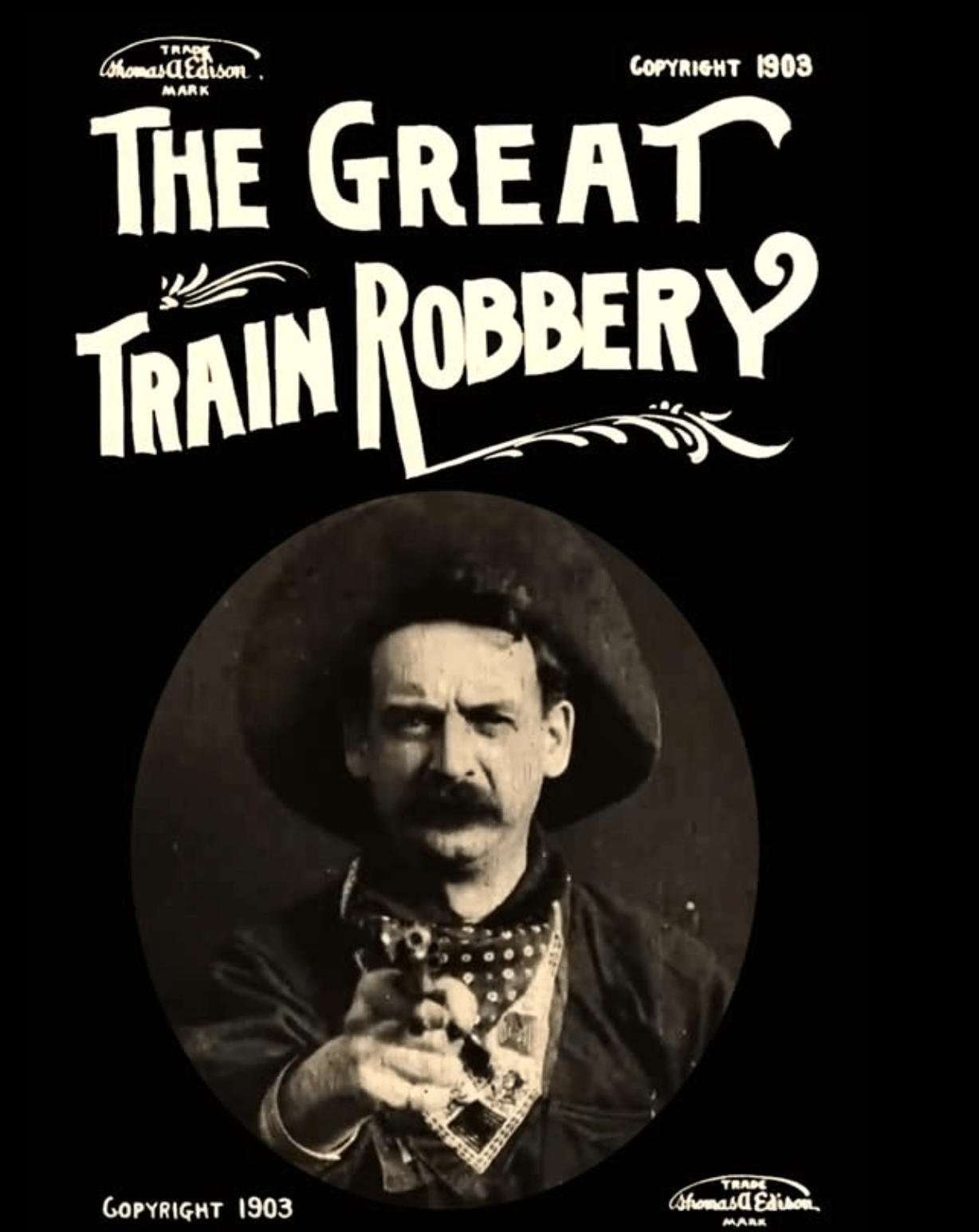

By 1907, the issue of whether films could influence behavior had surfaced in the media. The trade paper Motion Picture World reported a case of two teenage girls charged with shoplifting after they had just seen a movie about a thief. The editor warned of the danger crime films posed to children. A legal decision in 1908 gave the issue national publicity. Two boisterous westerns – The James Boys & Night Riders (now lost) were rejected for licensing in the state of Illinois due to “violence”. Highly unlikely any visual would shock an audience today. Screen violence in the silent era had a distinctly theatrical quality, generally shot at a full figure distance without intercutting any detail of wounds.

Six Nickelodeon operators, stalled in their release of The James Boys & Night Riders, sued, claiming that the story of the notorious outlaw brothers had already been depicted on stage and on arcade stereopticons. The Supreme Court of Illinois ruled against the plaintiffs citing that “the motion picture medium was more likely than other forms of entertainment to appeal to weak and immature minds…those classes whose age, education and situation in life specially entitle them to protection against the evil influences of obscene and immoral representation.” Chief Justice Cartwright described these films as “nothing but malicious mischief, arson, and murder.” The depiction of crimes that represents only the actions of the perpetrators are “immoral and their exhibition would necessarily be attended by evil effects on youthful spectators and therefore a threat to society.” The ban on the two outlaw westerns was upheld. The criminal must pay for his crimes became an early dictum. And show remorse.

As in the UK, states and municipalities across the US appointed their own censorship boards. Fees charged to each film’s distributor, up to $3 per reel reviewed, ensured that all such boards delivered handsome revenue to state coffers. In 1939 the State of New York earned $200,000 profit from purging Cinema of unwholesome content.

In 1916, to counter the confusion and contradictions of multiple censorship bodies, America’s National Association of the Motion Picture Industry (subsequently MPAA) announced it would police itself and issued a catalogue of prohibited material, referred to as the Thirteen Points: among them nudity, white slavery, violence, illicit love, gambling, alcoholism, and disrespect for the law. However, state and municipal censors were political appointees, a payoff to important party members or their wives. Nobody gives up those perks readily, so such bodies persisted for decades, even after the industry set up a detailed Production Code to prevent objectionable content. The studios paid lip service to the rules, but still sought to push the envelope, like Clara Bow skinny dipping in 1927’s HULA.

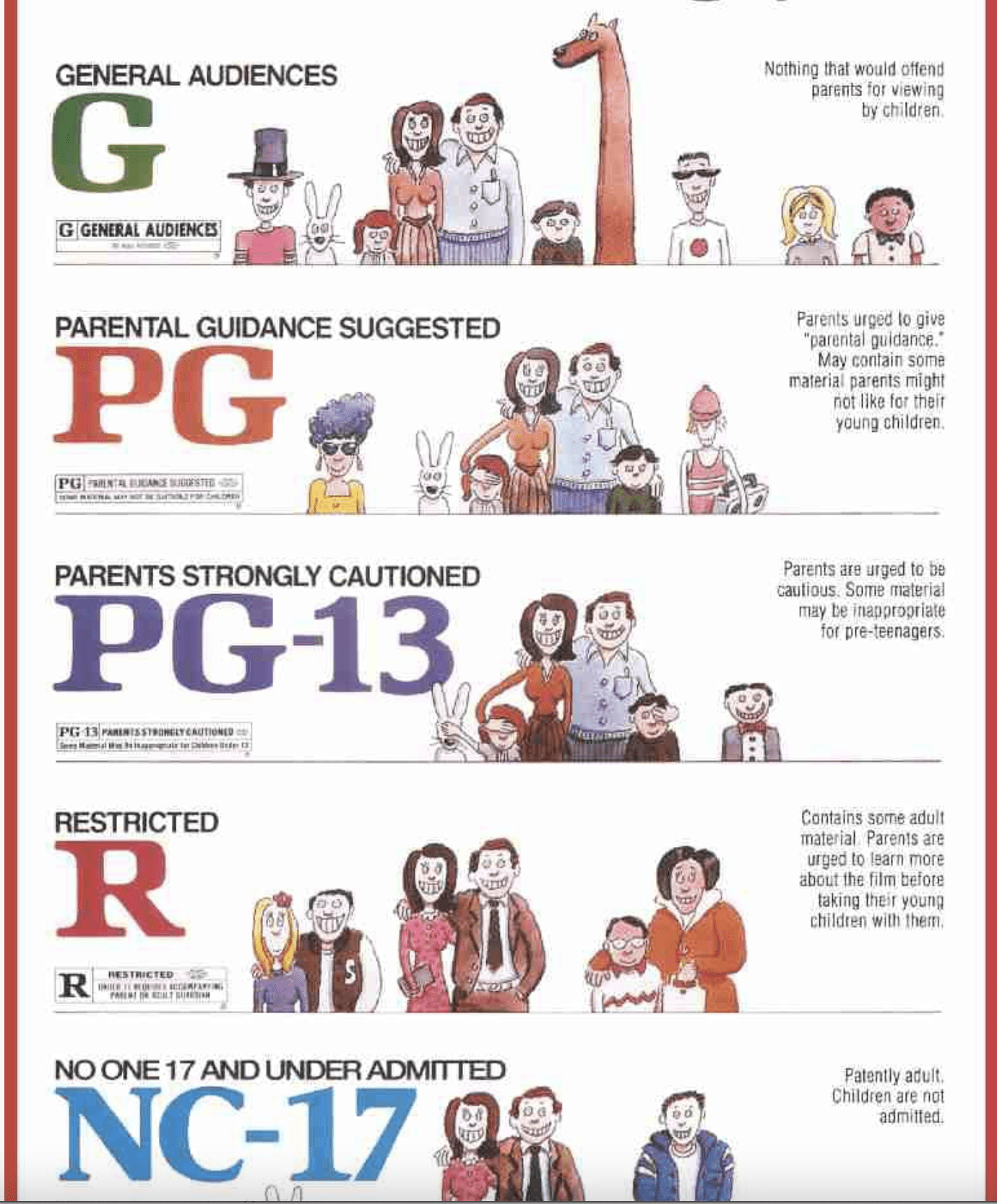

Criticism intensified from religious pressure groups, disturbed by the risqué dialogue of the new sound movies. The Catholic Legion of Decency, a mass membership association, threatened Hollywood with a nationwide boycott if it did not clean up its act. So, in 1934, the MPAA created its own enforcement arm, the Production Code Administration (PCA), with a devout Catholic, Joseph Ignatius Breen as its head enforcer. Fueled by religious and moral zeal, Breen’s iron grip on standards of Hollywood content remained in force till the mid 1950’s when independent producers began challenging his power and successfully released films with controversial themes without a Production Code seal. By the mid 1960’s the Code had lost all its enforcement power. Theaters were going to play pictures the public clearly wanted to see, with or without a PCA seal of approval. In 1968 President Johnson gave advertising executive and former campaign advisor Jack Valenti the task of making the Production Code more in tune with the times. Under Valenti’s leadership, a classification system for movies evolved that, with regular modifications, has worked quite well ever since.

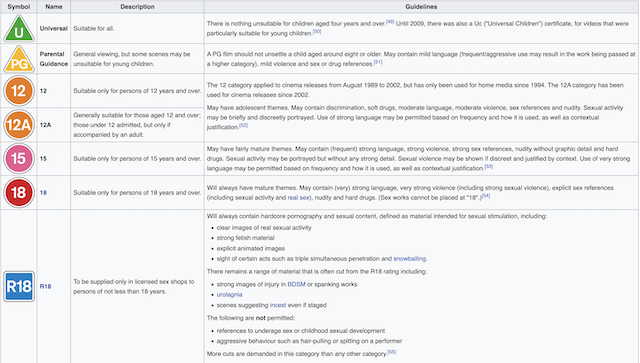

I find the British classification system more comprehensive in its advice to parents as to age suitability.

Censors reflects the society of their times. As a social history observer, I’m fascinated by the anomalies, contradictions, creative battles and covert agendas in the first 80 years of movie censorship. As background on the US Production Code, this site gives you all the salient information.

While Chief Censor Joseph I. Breen saw his work at the PCA as a positive mission with a socially uplifting outcome, cultural historian Thomas Douherty, in his biography of Breen, “Hollywood’s Censor: Joseph I. Breen and the Production Code Administration” was not so kind to the Code.

“Hollywood under the Code was variously, cumulatively, and intractably, racist, patriarchal, misogynistic, homophobic, capitalistic, and colonialistic.” He accused the Code of promoting “bourgeois, heteronormative, American-centric values upheld and celebrated from genre to genre, studio to studio.”

Between 1930 – 1934, studios sought to enhance depression afflicted box office by pushing the boundaries as much as they could until Breen took control of the Code. Here are a couple of examples that remained controversial.

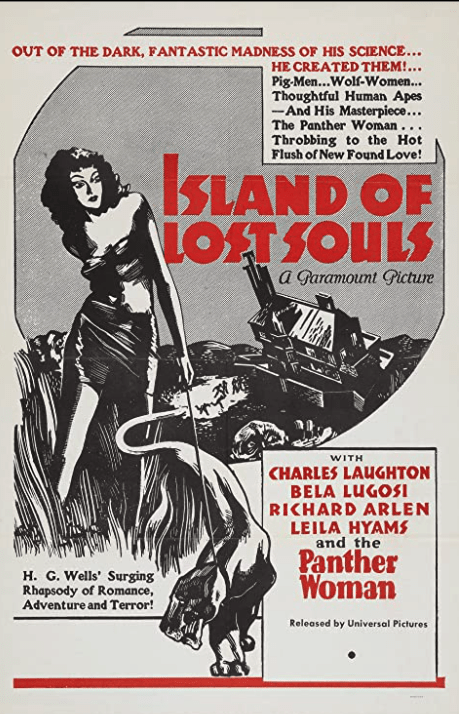

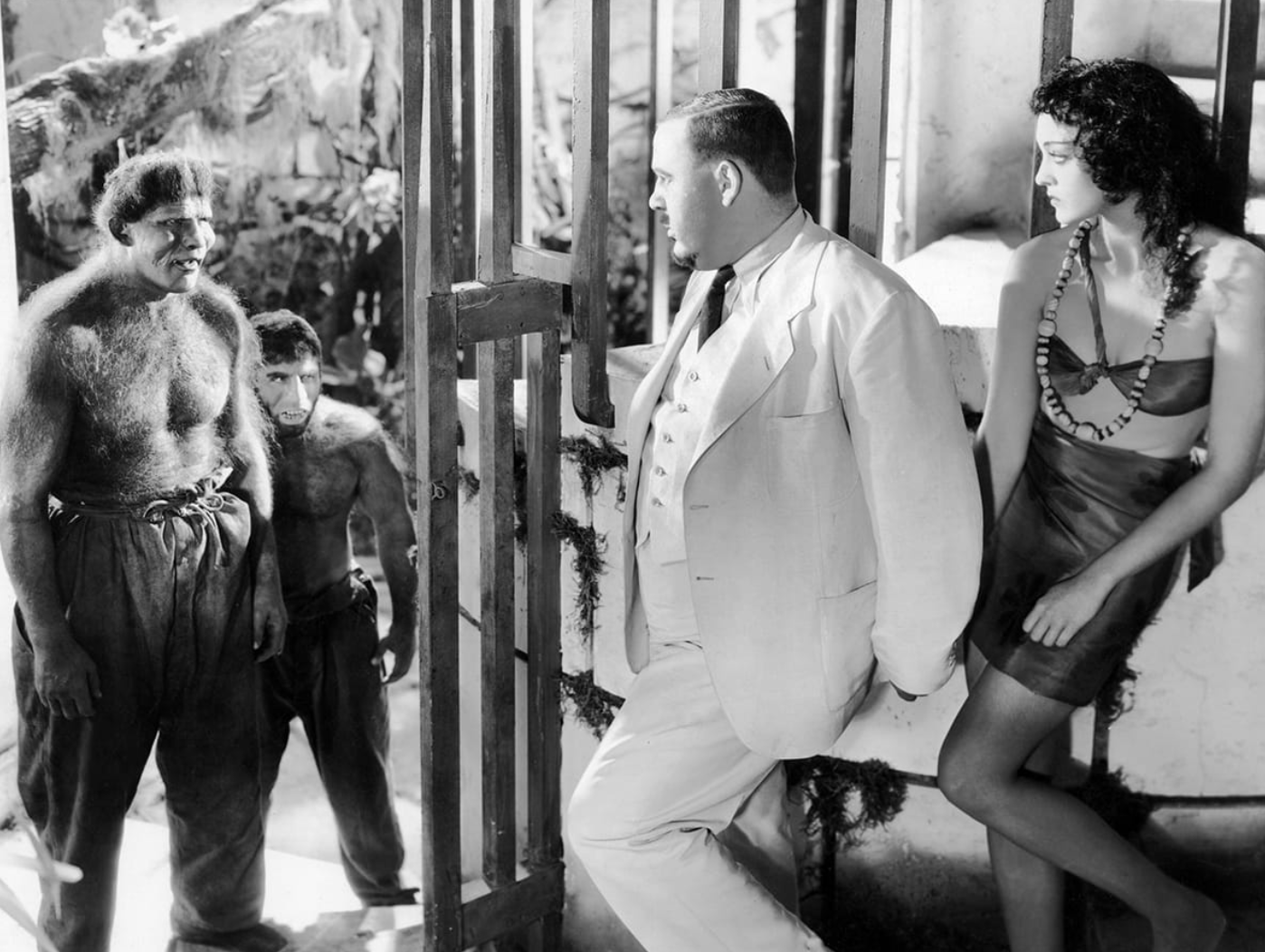

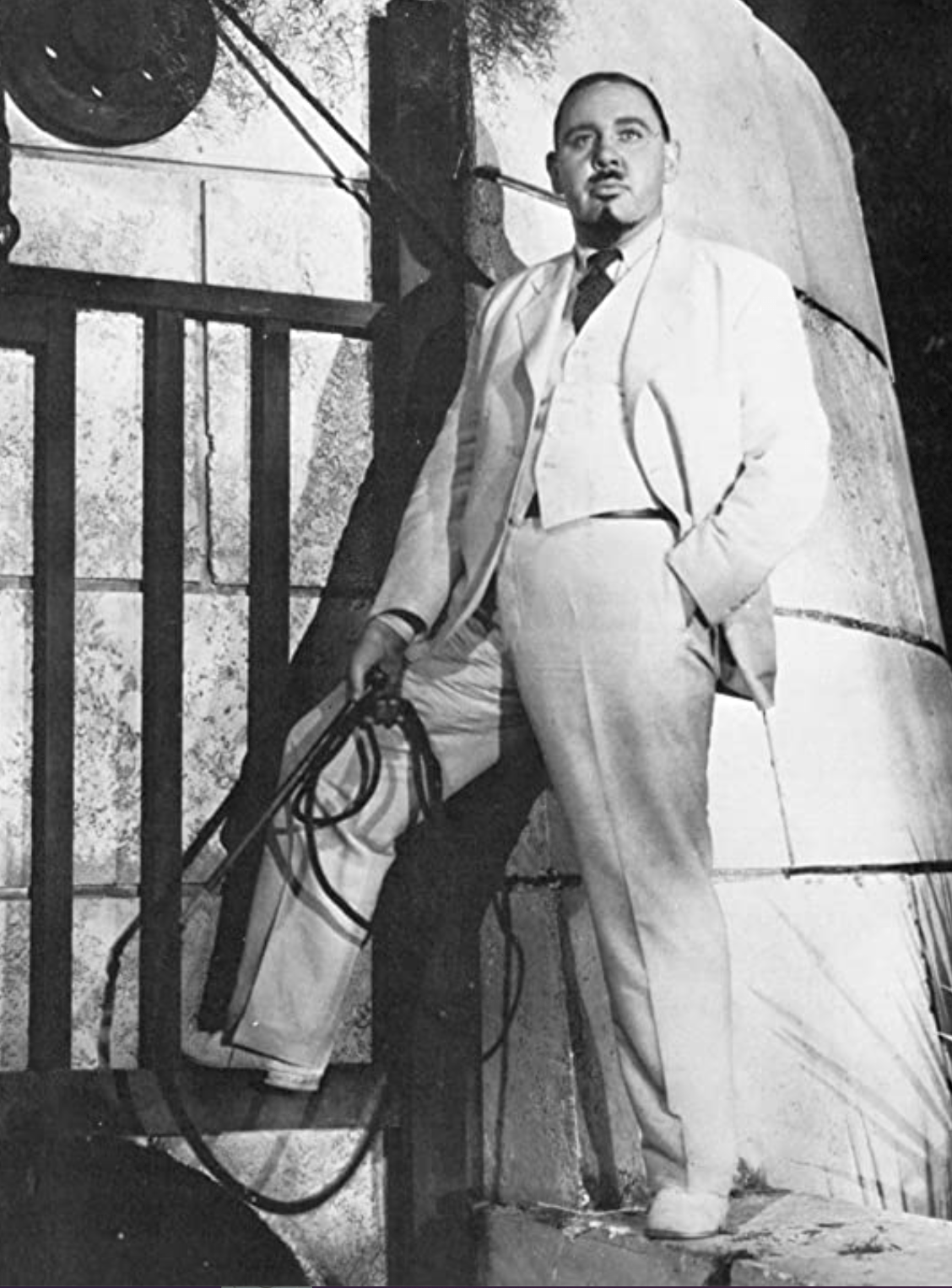

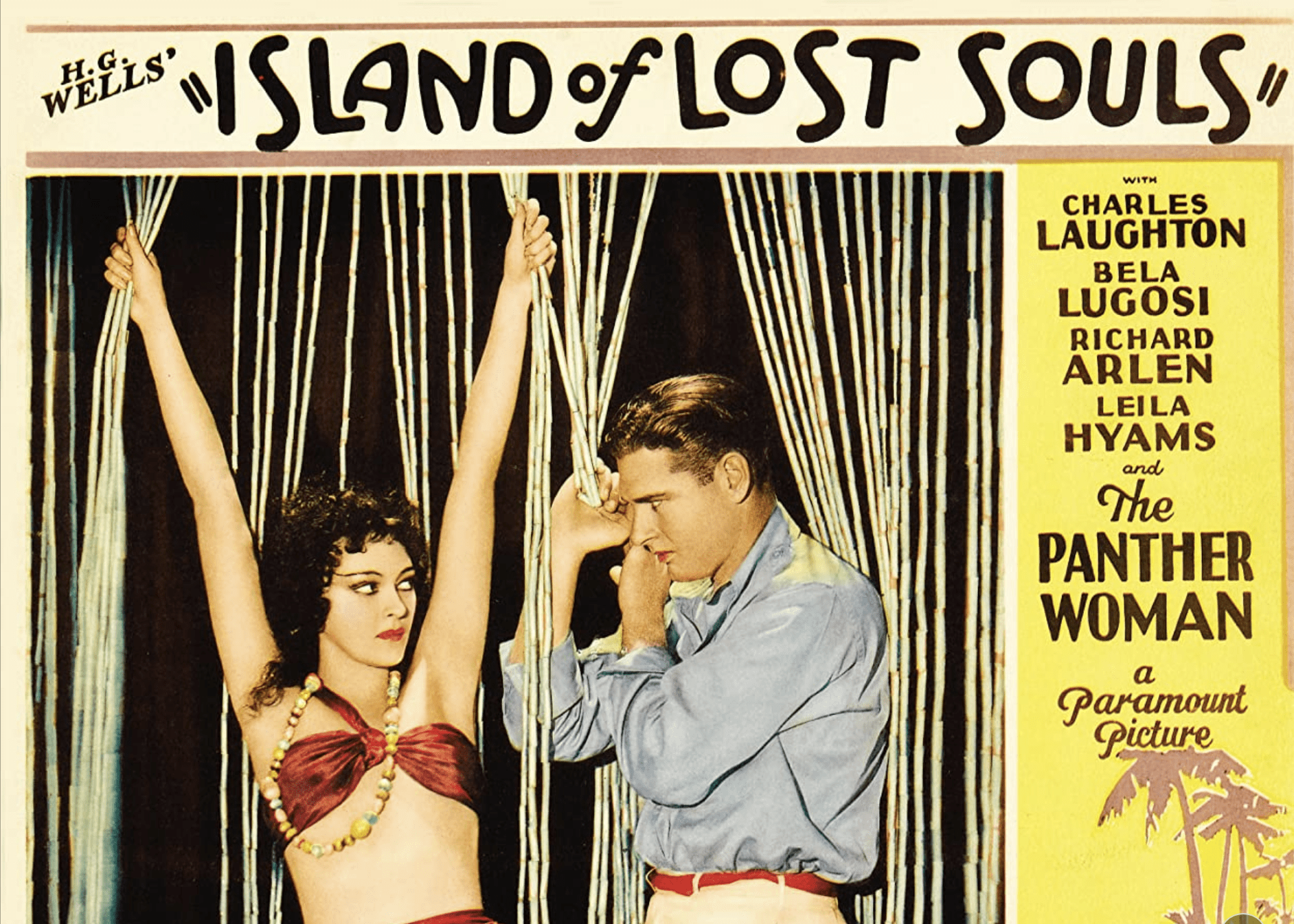

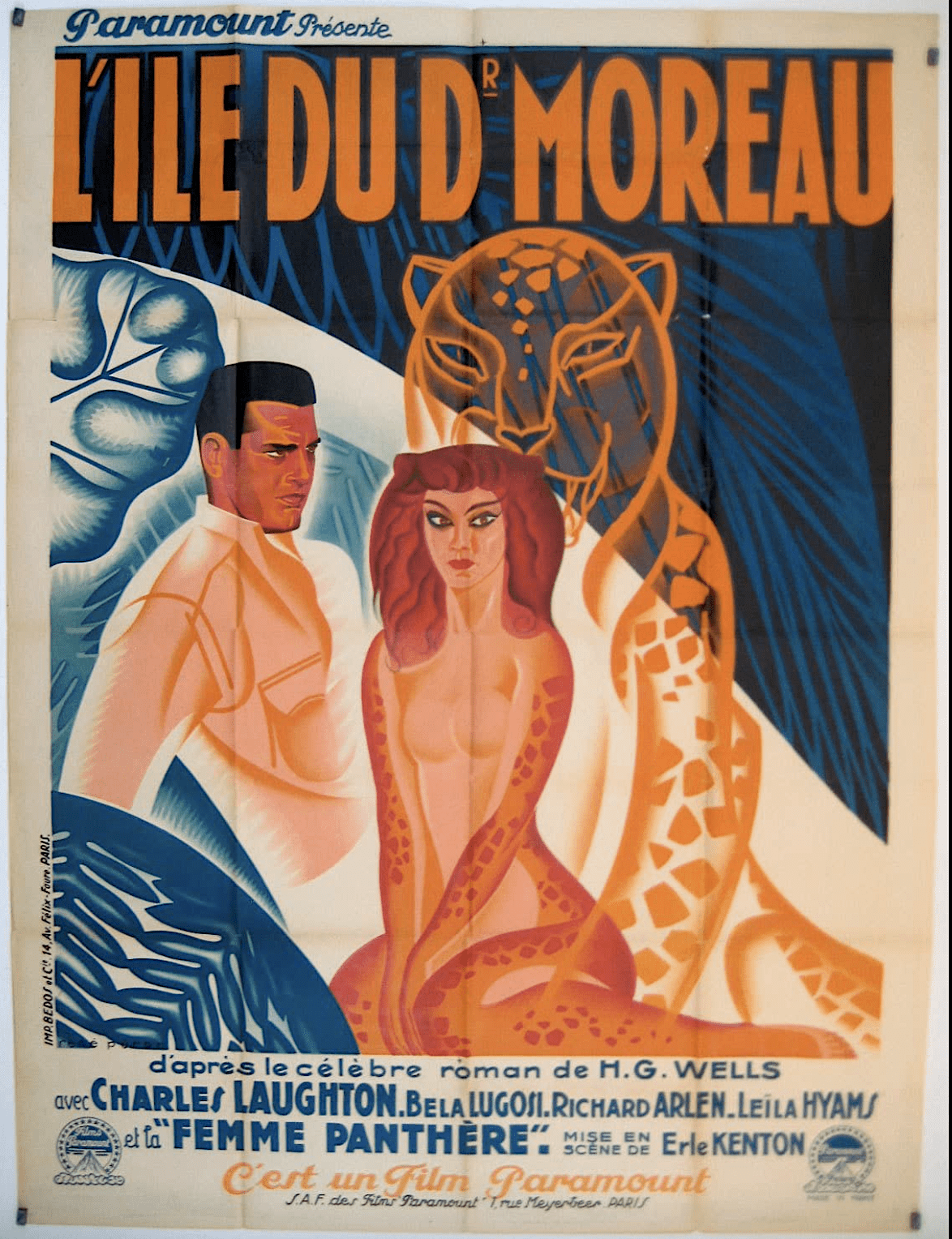

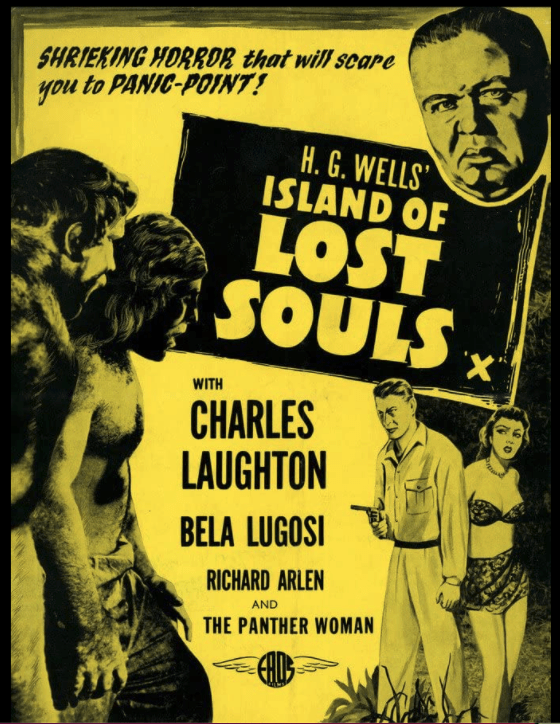

British and American censors from the 1930’s onwards had a common approach to what was permitted. Island of Lost Souls, in 1932, was a rare exception. The film was passed by the US Production Code (hereafter PCA) but banned repeatedly by the British Board of Film Censors till 1958, then only released with cuts.

The official reasons for the ban in 1933 were lost when the BBFC records were destroyed in the London Blitz of World War Two. However, their 1933 general report to parliament on the rejection of 23 films that year contains comments that might apply to Island of Lost Souls: “…psychological arguments treated too frankly for public exhibition” and “intense brutality and sordidness coupled with promiscuous immorality.” Island of Lost Souls was the first sound adaptation, after several silent versions, of the HG Wells’ cautionary tale of science run amok – The Island of Doctor Moreau. Acclaimed British stage actor Charles Laughton in his Hollywood debut plays a renowned scientist banished to a remote tropical island after the exposure of his vivisection experiments. Laughton avoided mad scientist cliches and played Moreau with a perverse sardonic charm.

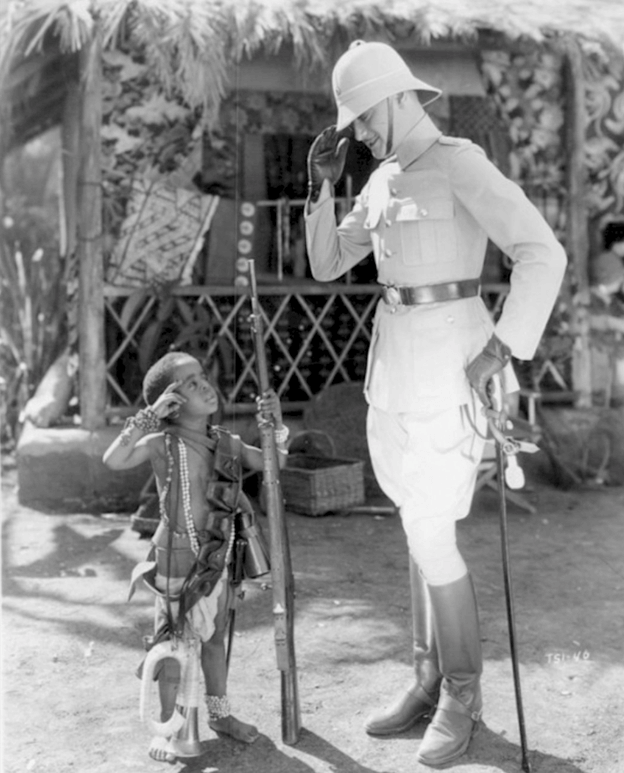

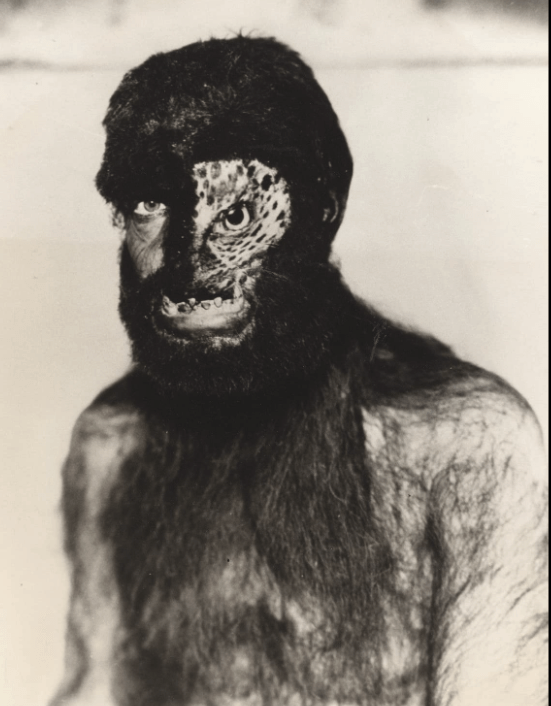

In a new laboratory, dubbed the House of Pain in Wells’ novel, Moreau continues his work to genetically engineer fully functioning human beings from the island’s animal population. But the results are only “Beast Folk” – human animal hybrids – much to the horror of a shipwrecked Englishman played by Richard Arlen, whom the Doctor encourages to mate with his latest creation – the Panther woman.

Such a provocative idea had squeaked by the PCA due to lax enforcement prior to 1934, but to the church going middle aged British censors, the mere suggestion of “bestiality” coming from a scientist who asks “Do you know what it means to feel like God?” was enough to give them a heart murmur. Then there was the vivisection scene, only a 5 second wide-shot, in which no actual vivisection is seen, but preceded by several off screen howls of pain. Anti-vivisection legislation had been on the statute books for 50 years. Worse, this was vivisection of a human-animal hybrid! The portrayal of cruelty to animals in feature films released in Britain was explicitly forbidden. It was a case of controversy overload.

The depiction of biological evolution under human control was “repulsive” and “unnatural”, as was the implication that God created Man out of lower animals, in direct conflict to Biblical teaching in the Book of Genesis. Affront to religion, In suspect, was a significant factor in the banning. In response to the claim that the film was against nature, Elsa Lanchester, (Mrs. Charles Laughton) reportedly said “Of course it’s against nature. So’s Mickey Mouse!”

What was it that went over the heads of the PCA, but resonated strongly with the BBFC, the supervising censor board of the British Empire and its colonial possessions in Asia and Africa?

In Charles Laughton’s white suited Master cracking a whip to control and civilize the natives, the BBFC saw the film as a colonial allegory, implicitly critical of the British Empire’s control over its African and Asian possessions. All the colonials in the film wear traditional white suits, whereas in Wells’ novella they were dressed in ‘dirty blue flannels.’ Wells described the Beast-Men as ‘islanders’, whereas the movie’s European characters refer to them as ‘natives.’ The film’s politics, albeit embedded in a horror film, was clear to the examiners. When Doctor Moreau ends his examination of Lota, the Panther Woman, whose “stubborn beast flesh” is returning, with a sadistic promise: “this time I’ll burn out all the animal in her!”, the implied racism of the character was an affront to the dignity of colonial administrators.

At a time when independence movements were growing in Britain’s colonies, it was hard for the BBFC not to view, as subversive allegory, the climactic revolt of the Beast-Folk, who murder their white suited Master with the same surgical instruments he used on them. Although it was banned in the UK, Australia passed the film for white audience, but with the restriction (NEN) Not to be Exhibited to Natives.

A brief digression into institutionalized racism in censorship.

From 1926 onwards, rules relating to matters of race were strict in the British colonies of Hong Kong, Singapore and India, as pro- independence demonstrations gradually spread across the Empire.

Consider these interesting quotes from the guidelines issued to colonial administrators by the BBFC:

- “Any film denoting Bolshevist or mob violence. The Chinese are easily worked up and there is quite enough mob violence going on at the moment.”

- “Any film showing the white man in a degrading or villainous light.”

- “Any film showing white women in indecorous garb or positions, which would tend to discredit our womenfolk with the Chinese.”

- “Stories showing any antagonistic or strained relations with the coloured population of the British Empire, especially with regard to the question of sexual intercourse, moral or immoral, between individuals of different races.”

- “Any film that deals with racial questions, specifically the intermarriage of white persons with those of other races.”

There were also location-specific restrictions. Pictures reflecting badly on the natives of India were banned in Hong Kong, because a significant portion of the Hong Kong Police were of Indian ethnicity.

The make-up effects used to create the multi ethnic Beast-Men contributed to the film being banned in several countries.

In America, when Island of Lost Souls was submitted to the PCA in 1941 for re-release approval, they corrected their earlier lapse of doctrinal judgement; all dialogue suggesting in any way that Dr. Moreau had created the Beast-Men had to be removed. Only God can create, not man. By making the Beast-Men just God’s creatures who happened to live on the island, the PCA eliminated the essence of HG Wells book which debated scientific ethics. Wells hated the film, because it introduced a totally new character not in the novel, the Panther Woman, to provide sexual tension. He publicly applauded the BBFC’s ban.

When the BBFC introduced the “X” Certificate in 1951, Paramount resubmitted Island of Lost Souls believing, two decades later, it would be passed for the new adults only classification. Wrong. The BBFC expressed its disdain: “The film is old and bad; whatever might be the case for permitting the theme of this film in a modern production, there is no ground whatsoever for permitting this dated monstrosity to be revived under cover of our ‘X’ Certificate.” It “would do our ‘X’ a lot of harm.” The French had no problem with its release.

Paramount tried again in 1957, receiving the response from the BBFC that “the film was no less repulsive than when it was viewed before…totally unacceptable for public exhibition in this country.” Paramount then submitted an extensively edited version, which the BBFC was initially reluctant to view in the light of the backlash from religious leaders to the flood of “X” Certificate horror films that followed the success of Hammer’s Dracula and Frankenstein remakes. BBFC Secretary John Nichols stated: “There has been a considerable hardening of responsible public opinion against horror films, and we certainly cannot relax our standards – indeed, a little tightening up is desirable.” After further wrangling, further cuts were made and an “X” Certificate was issued.

So it remained till 1996 when an uncut version was classified “12” for video release, because “it was surprising to see how well the horror holds up”. In 2011, the uncut DVD release was reclassified PG, on the grounds that children were seeing more frightening monsters on Doctor Who and Harry Potter.

The film benefitted from expressionistic cinematography by Karl Struss, who had shot Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde the year before. The director was Erle C. Kenton, a former teacher who acted in Mack Sennett silent comedies, and graduated to director, developing a reputation for bringing a film in on time and on budget. He was paid $750 per week to direct Island of Lost Souls. By 1960, he had accumulated 144 directing credits, finishing his career like many prolific B Movie directors in television.

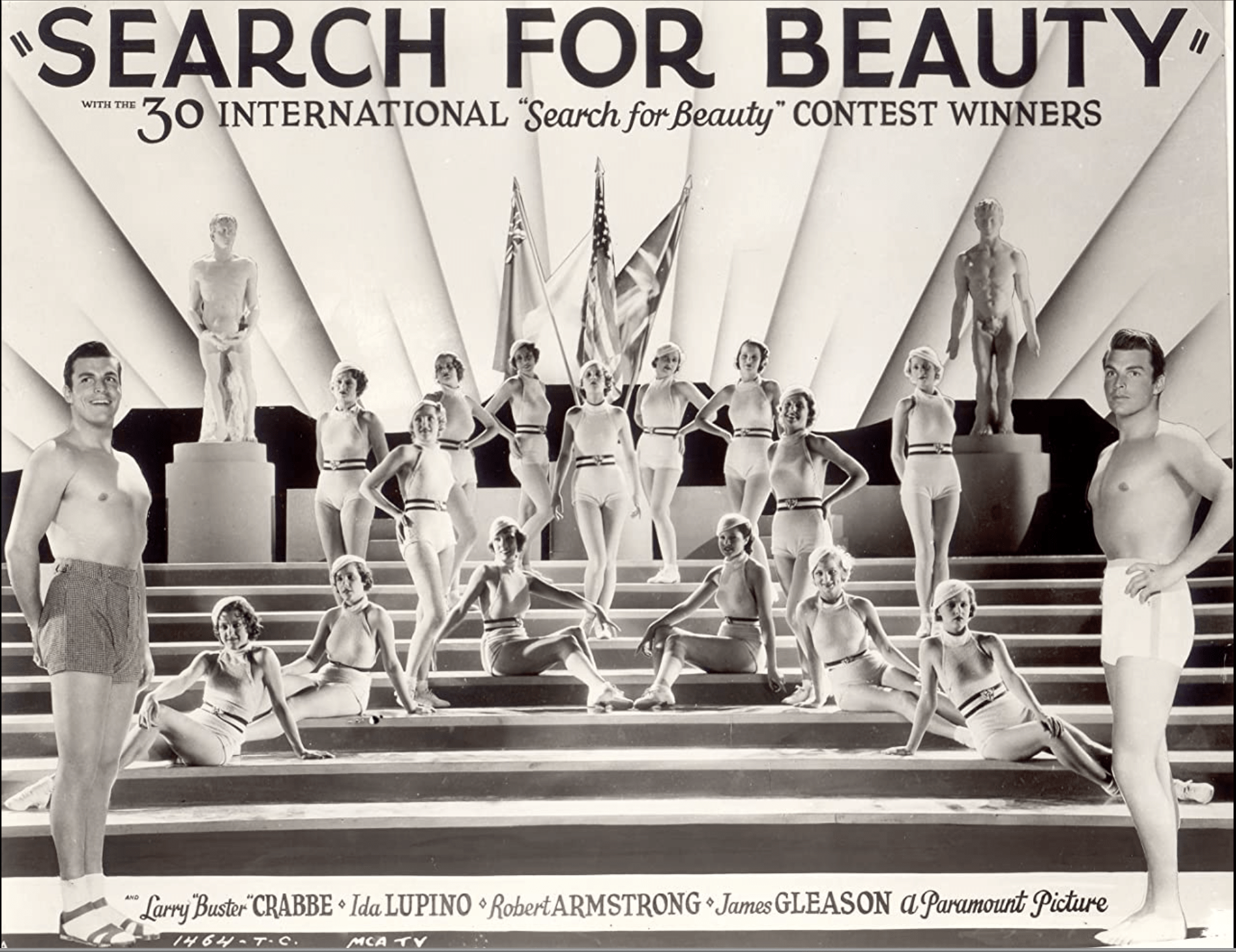

Like many perceived journeymen, his work was underrated. In 1942 he directed two of Abbott and Costello’s best comedies Pardon My Sarong, and Who Done it? His Universal horror movies House of Dracula (1945), House of Frankenstein (1944) were solid examples of low budget ingenuity keeping a tired horror franchise alive. While Island of Lost Souls is considered his one true classic, he has another claim to fame – Search for Beauty.

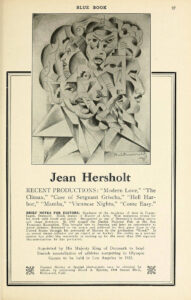

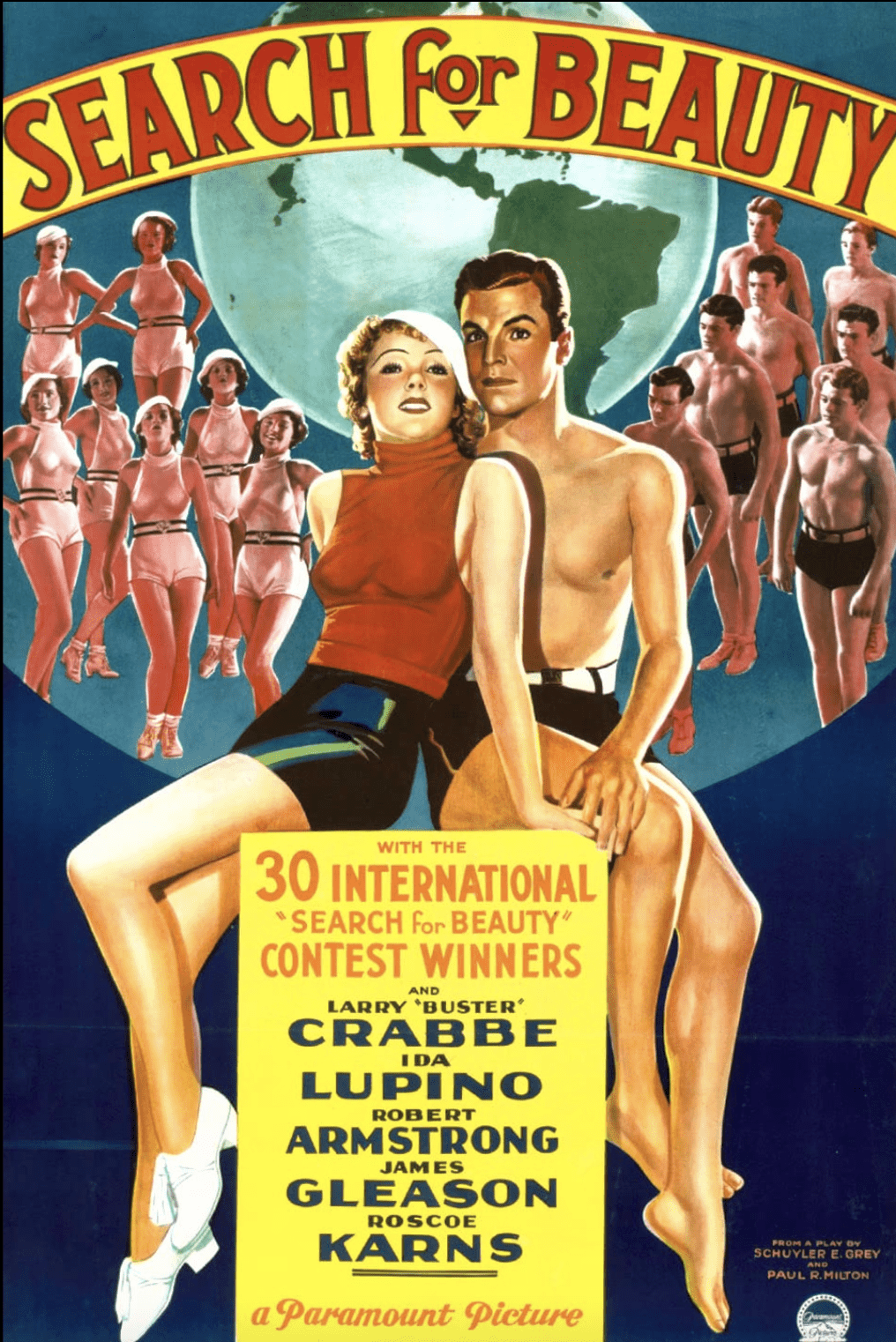

Erle Kenton saw the days of flexible interpretation of the Hays Code would soon be over. Under the incoming management of the PCA. any film to be released after July 1st 1934, would be subject to much stricter controls. Erle set out again to make a picture that would push the envelope, and get it into release before the before the door of permissiveness closed. The genre he chose was sex comedy.

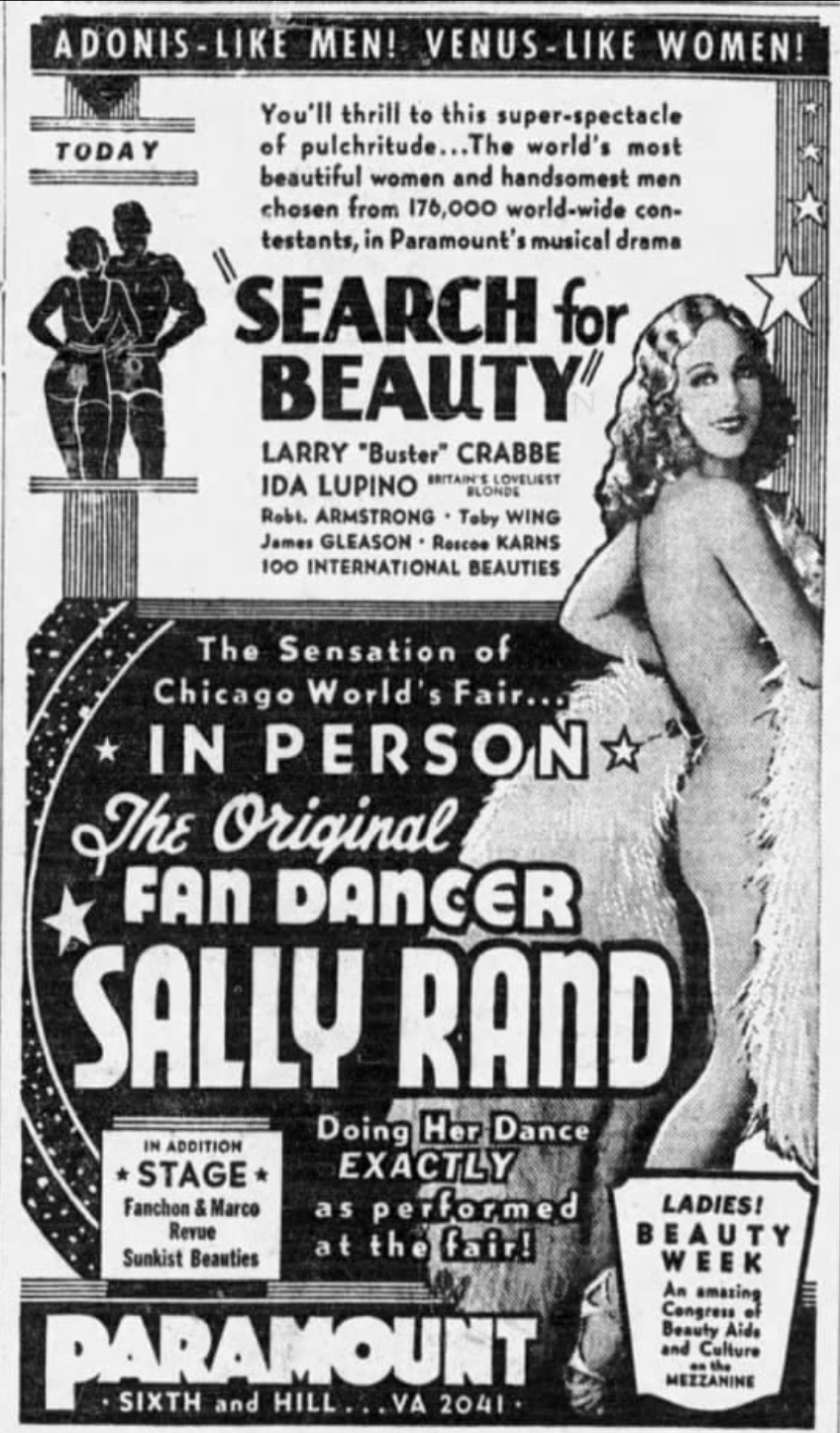

The premise was based on a play: Three comedically characterized con artists dupe two Gold Medal Olympians into serving as editors of a new health and beauty magazine which is only a front for scandal stories and salacious pictures. With the Olympians’ names on the Health & Exercise front cover, their smutty magazines will pass through the mail with innocent wrapping without being seized by the federal authorities and thus earn a fortune. A scheme that has much in common with Paramount’s agenda for the movie too.

But the Olympians heroically turn the tables and put the tricksters out of business. Decency triumphs! A moral tale, that conveniently offers constant opportunities to display male beefcake and female pulchritude in revealing athletic costumes and lingerie.

Is that a wardrobe malfunction I see before me? (Or is it by design?) The sheer number of scenes of undress convinces me that director Erle Kenton set out to make – while he still could – the 1934 equivalent of a skin flick, perhaps a proto-Porky’s without the nudity, where the lure for the audience, both male and female, is to ogle beautiful bodies.

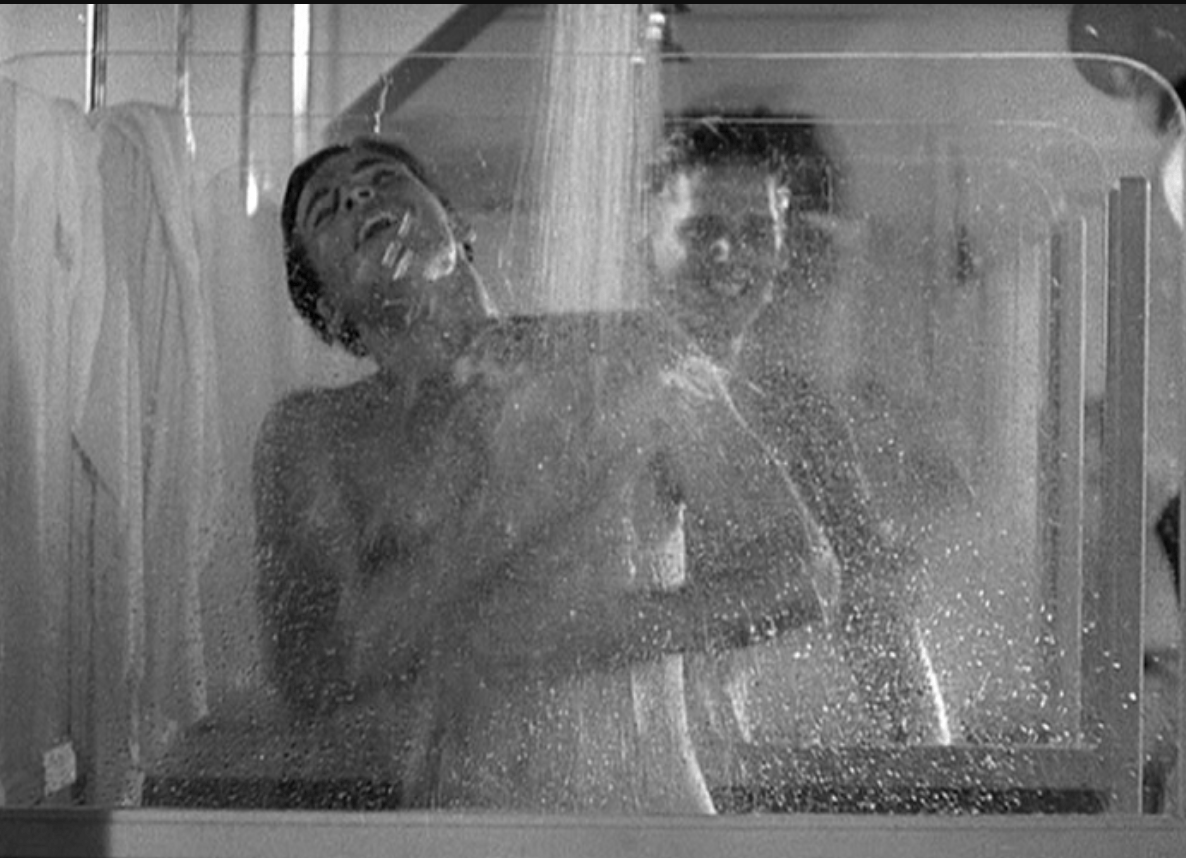

You will not see such figure-contouring female costuming in a Hollywood film after this. Erle Kenton knew how to skirt the rules, putting sex into the audiences’ mind in non-sexual situations. Scenes of physical exercise can always justify a subsequent shower scene, right? Maybe two.

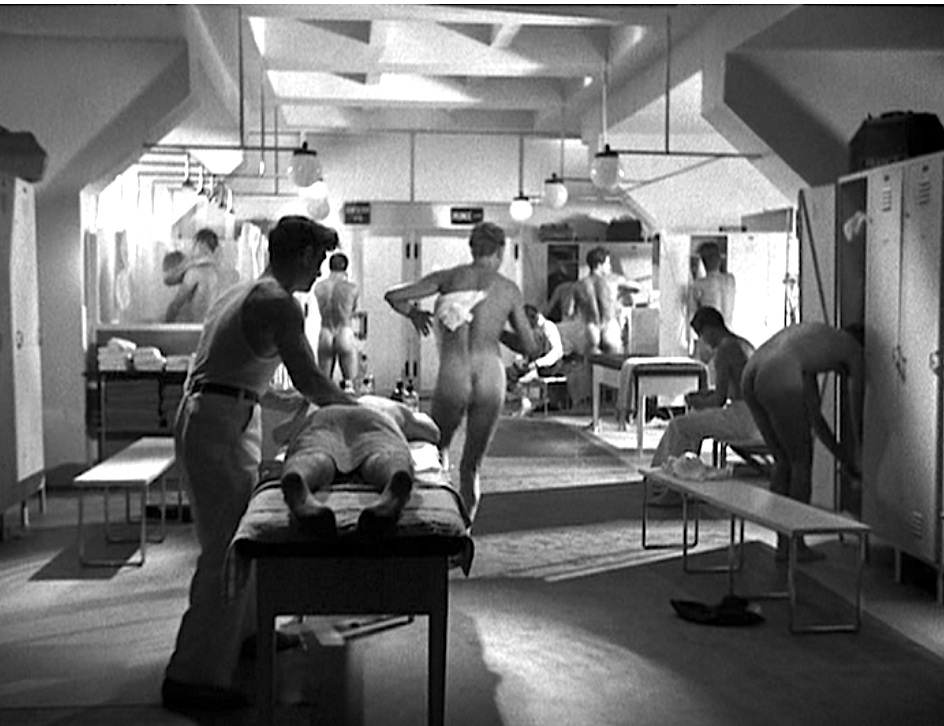

The locker room scene with four bare butts was a rarity even in Pre-Code. Perhaps Kenton was trying to set a precedent. Good luck with that under the Breen regime. Several scenes were cut out when the film was submitted for re-release years later.

Gay cinephiles have told me Search for Beauty had strong appeal to the closeted gay and lesbian community of America, a significant segment of the movie-going audience of which Paramount was privately well aware: an audience that dared not speak its name, you might say, but yearned for movies that in some way spoke to them.

Gay cinephiles have told me Search for Beauty had strong appeal to the closeted gay and lesbian community of America, a significant segment of the movie-going audience of which Paramount was privately well aware: an audience that dared not speak its name, you might say, but yearned for movies that in some way spoke to them.

Equally attractive to gay and straight audiences alike was Buster Crabbe in his first leading role. Before entering acting, Crabbe was an actual Olympic bronze medalist in 1928 and a gold medal winner in 1932. A one-time Tarzan, he would go to star in the popular Sci- Fi serials Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon.

Kenton partnered him with a British actress in her first Hollywood role – Ida Lupino. Over a 50 year career she notched up 105 movie and TV roles, before becoming one of the few women in Hollywood to maintain a career as a director, traditionally a male preserve. Two of her films Outrage (1950) and The Hitchhiker (1953) are registered by the Library of Congress as “culturally, historically or aesthetically” significant.

Search for Beauty is in its own way culturally significant because of deliberate objectification of the male as much as the female body.

Consider which part of Buster Crabbe is the focus of the lady’s attention:

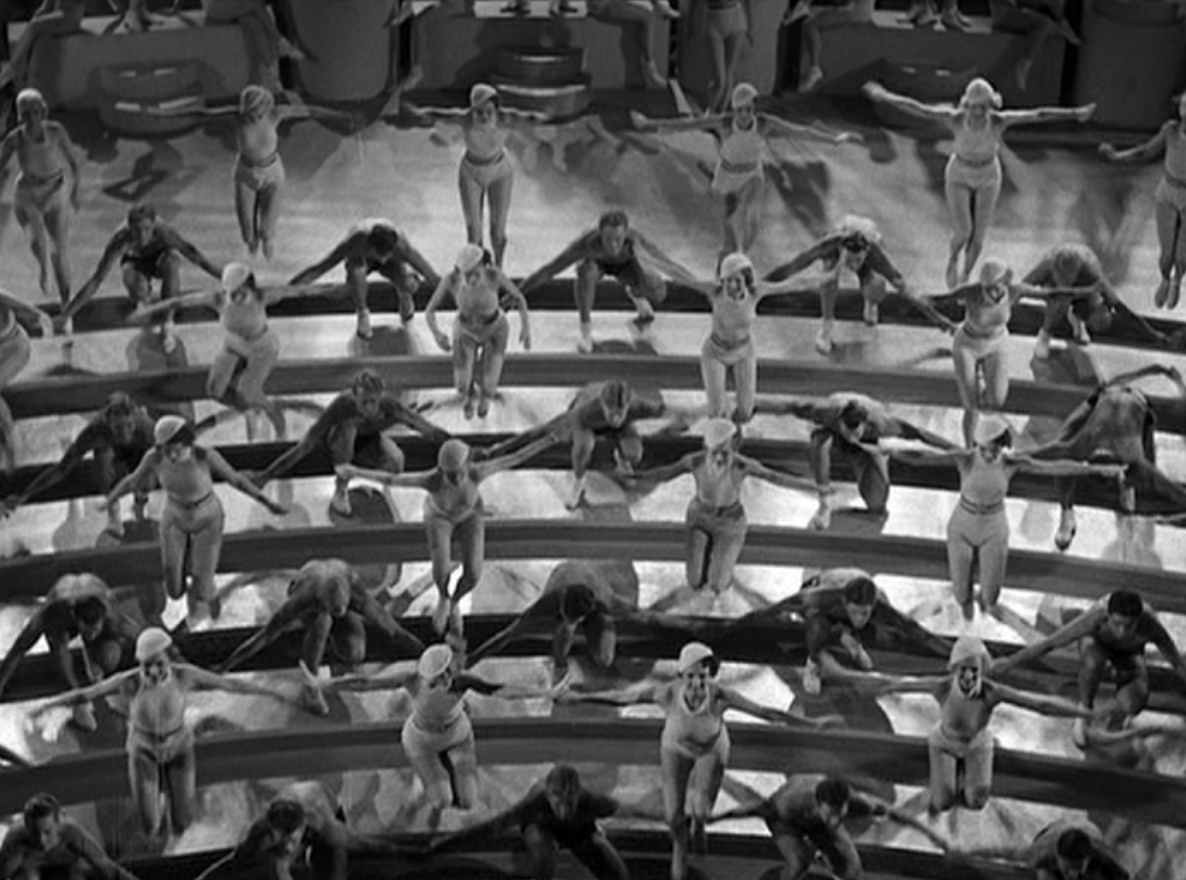

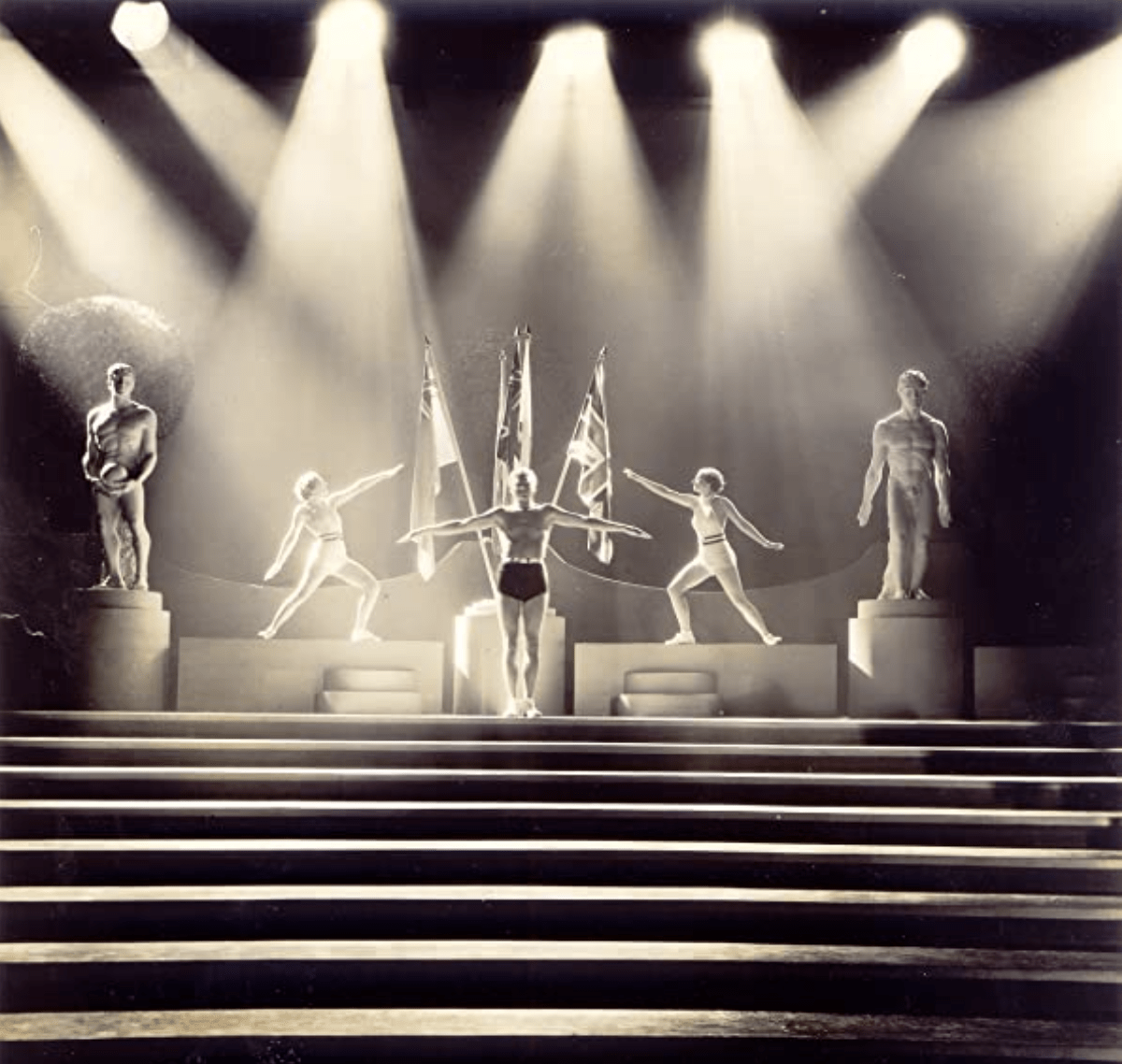

The film’s climax of massed athletes performing calisthenics in a Busby Berkeley-esque musical parade has a curiously fascist tone.

Did Leni Reifenstal screen a print of Search for Beauty while planning the fascist imagery her Olympia movie? There are oddly prescient camera angles in the triumphant Parade of Beauty sequence.

Beautiful specimens of humanity, all with shaved armpits, marching together for health through calisthenics! Not a black face amongst them, of course. But that was Hollywood back then.

Is the Sieg Heil accidental? I assume that Paramount had high hopes for Search for Beauty in Germany one year after the Nazi party, a strong advocate of physical fitness, had taken control of the country. Germany was an important foreign market. For six more years most major studios would remain uncritical of Nazi atrocities to protect that revenue stream. Double standards rule in Hollywood. Paramount pitched Search for Beauty as a moral fable. This poster for a Chicago theater, highlighting a live burlesque act as the supporting program film, is a telling indication of Paramount’s grasp of the picture’s core audience.

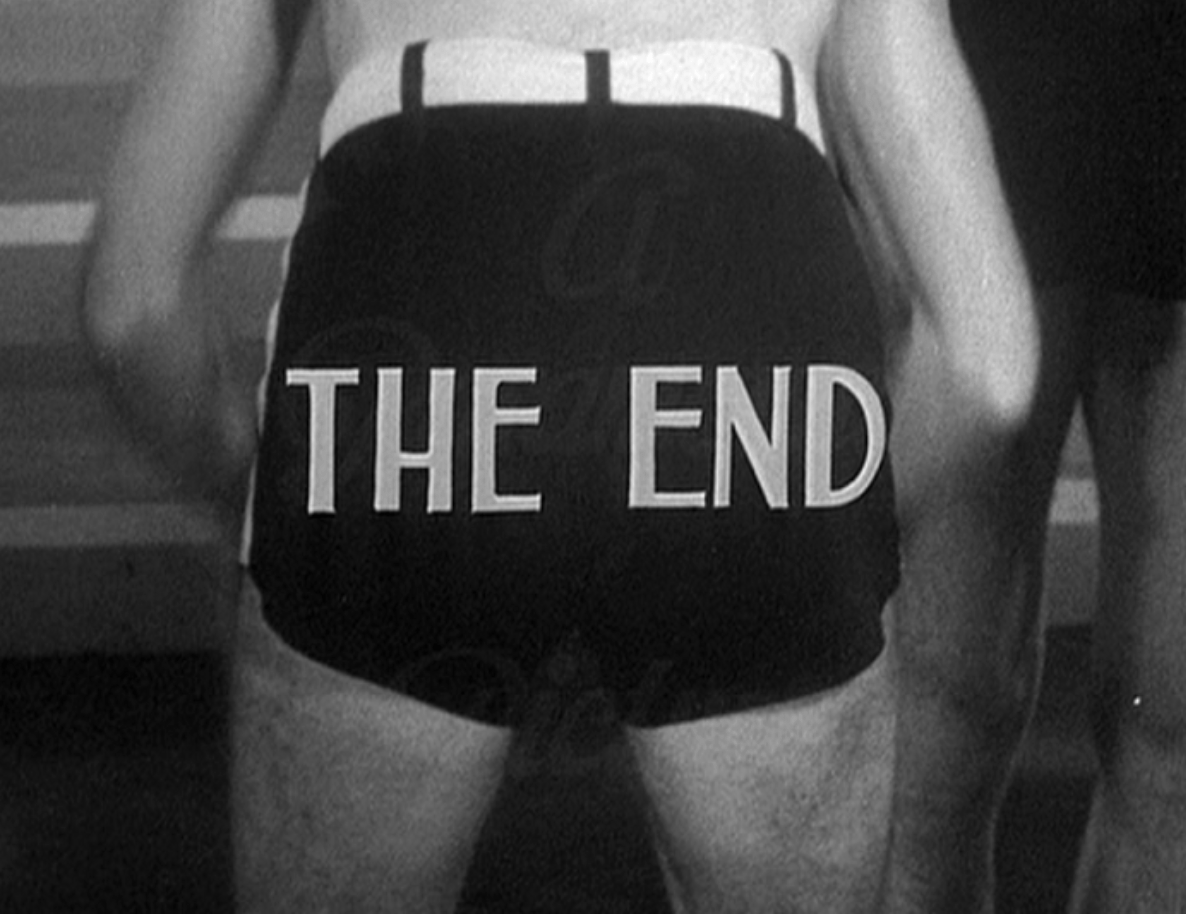

Director Erle Kenton, for his part, made Search for Beauty as an irreverent lampoon of American prudery, indicated by his choice of final shot.

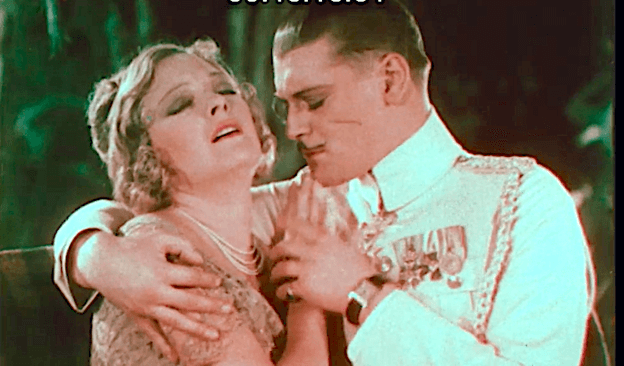

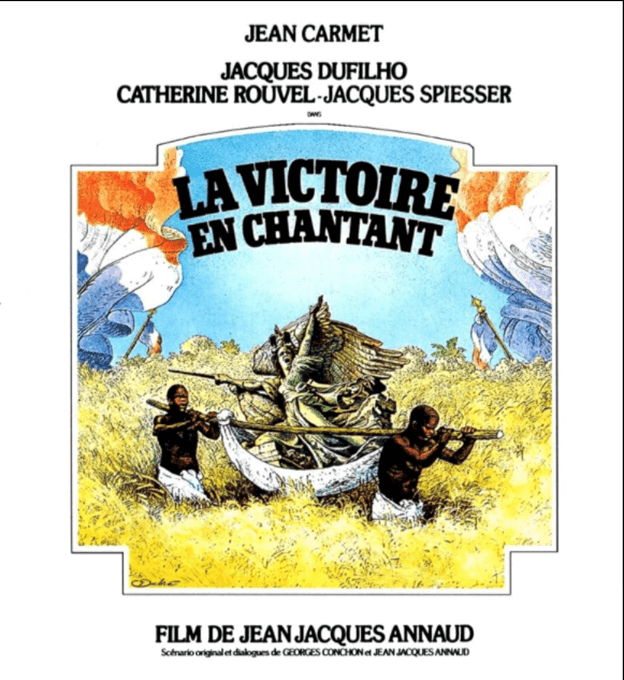

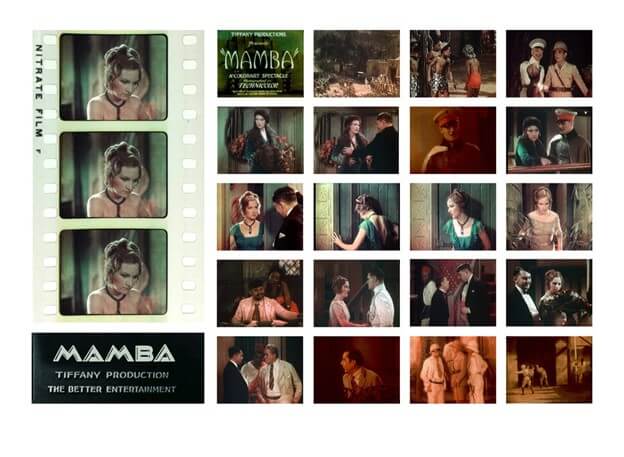

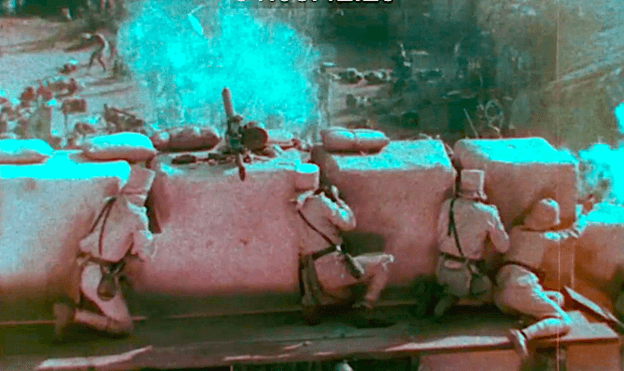

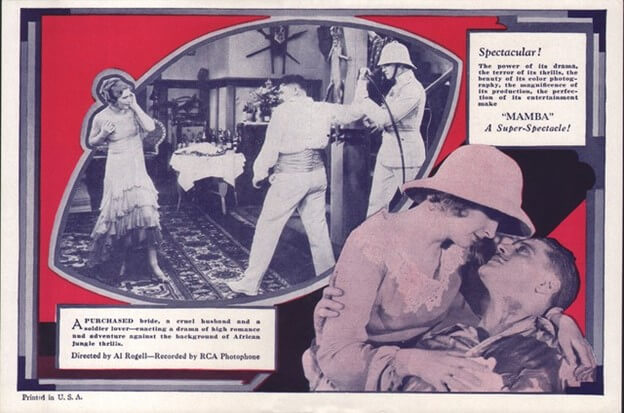

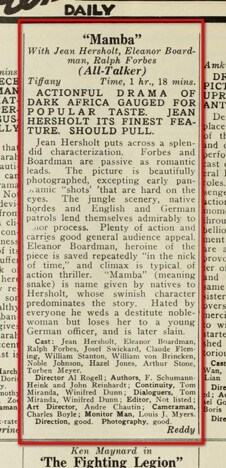

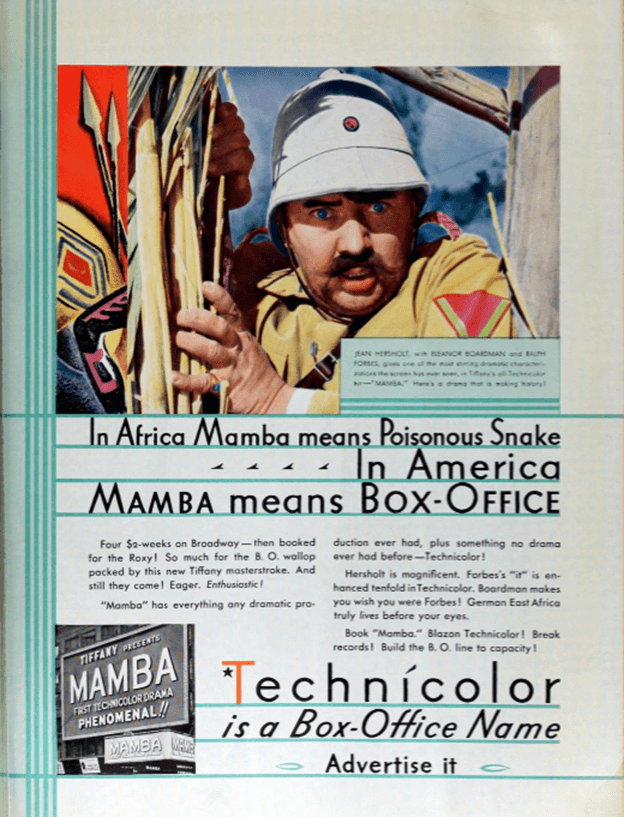

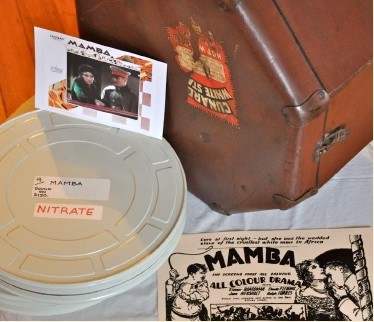

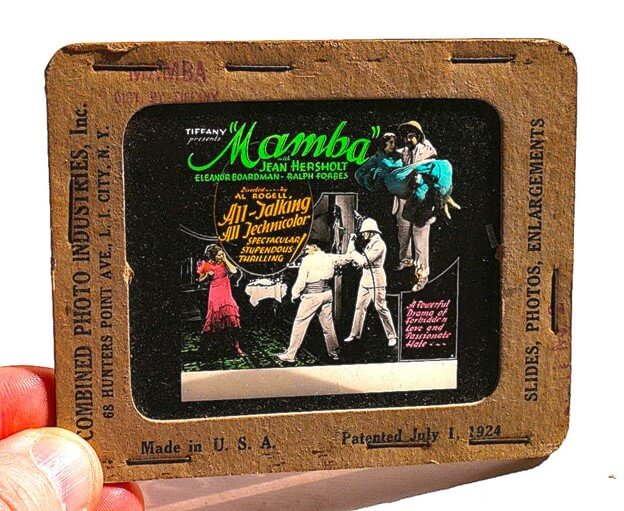

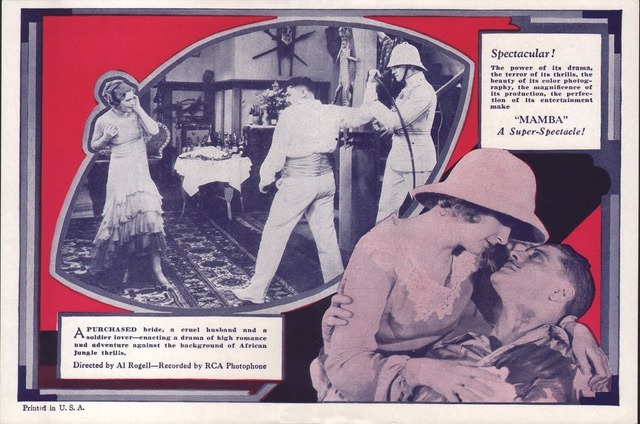

In the silent era, keeping sex off the screen was the focus of censors. With the arrival of sound and color, violence increased its ability to shock. In March 1930, the Tiffany Production MAMBA gave audiences the first opportunity to see blood in 2-Strip Technicolor.

They also got to see miscegenation, misogyny, whip-wielding threats of threats of marital rape, and natives killing white men! Lurid subject matter that got the guardians of morality clutching their pearls.

MAMBA, and the code breaking films described earlier, resulted in a hardening of the production code under Joseph Breen. Adding weight to restrictions on explicit violence was the popularity of gangster movies like Scarface and Public Enemy, in which multiple characters die in a hail of bullets, the sound of which was a novelty, that echoed through the theater, inducing a visceral impact not experienced in silent cinema.

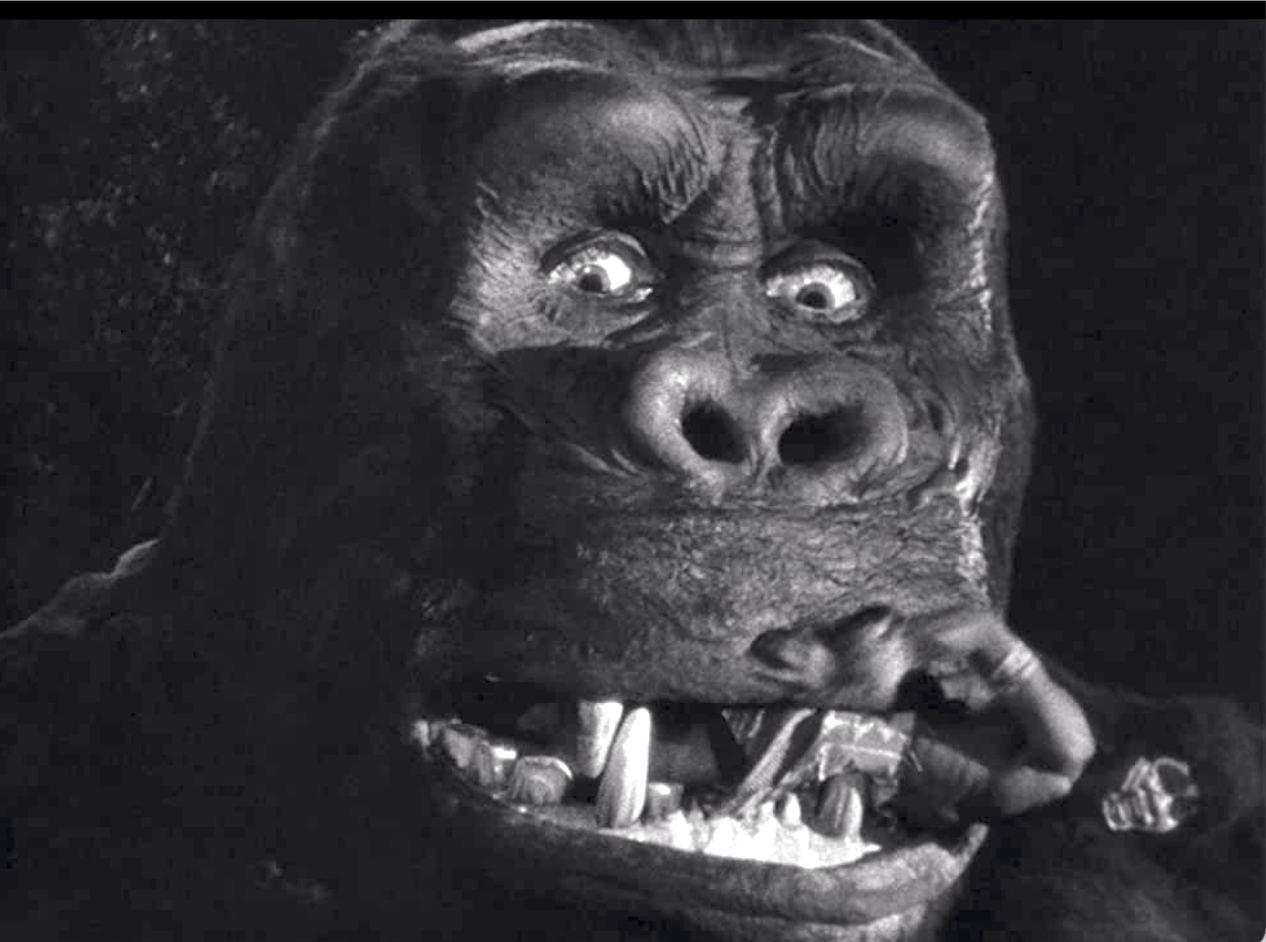

Sound triggered a legitimate question for the censors of the world: Does screen violence have a priming effect on cognitive and emotional response? Can a violent movie incite a cinema goer to commit a violent act? That debate continues today. The earliest censorship codes decided to prohibit explicit depiction of wounds and mortal agony. For five decades, censors believed that detailed violations to the integrity of the human body were too confronting to the psyche of adult audiences. Characters could have a cut lip, or bleed politely from a flesh wound. Violence done to the head or face, the epicenter of our intelligence and personality, was regarded as more confronting than violence directed at a clothed part of the body and had to be handled with discretion. After the Production Code became rigorously enforced in 1934, previously approved violence was cut from re-releases of King Kong.

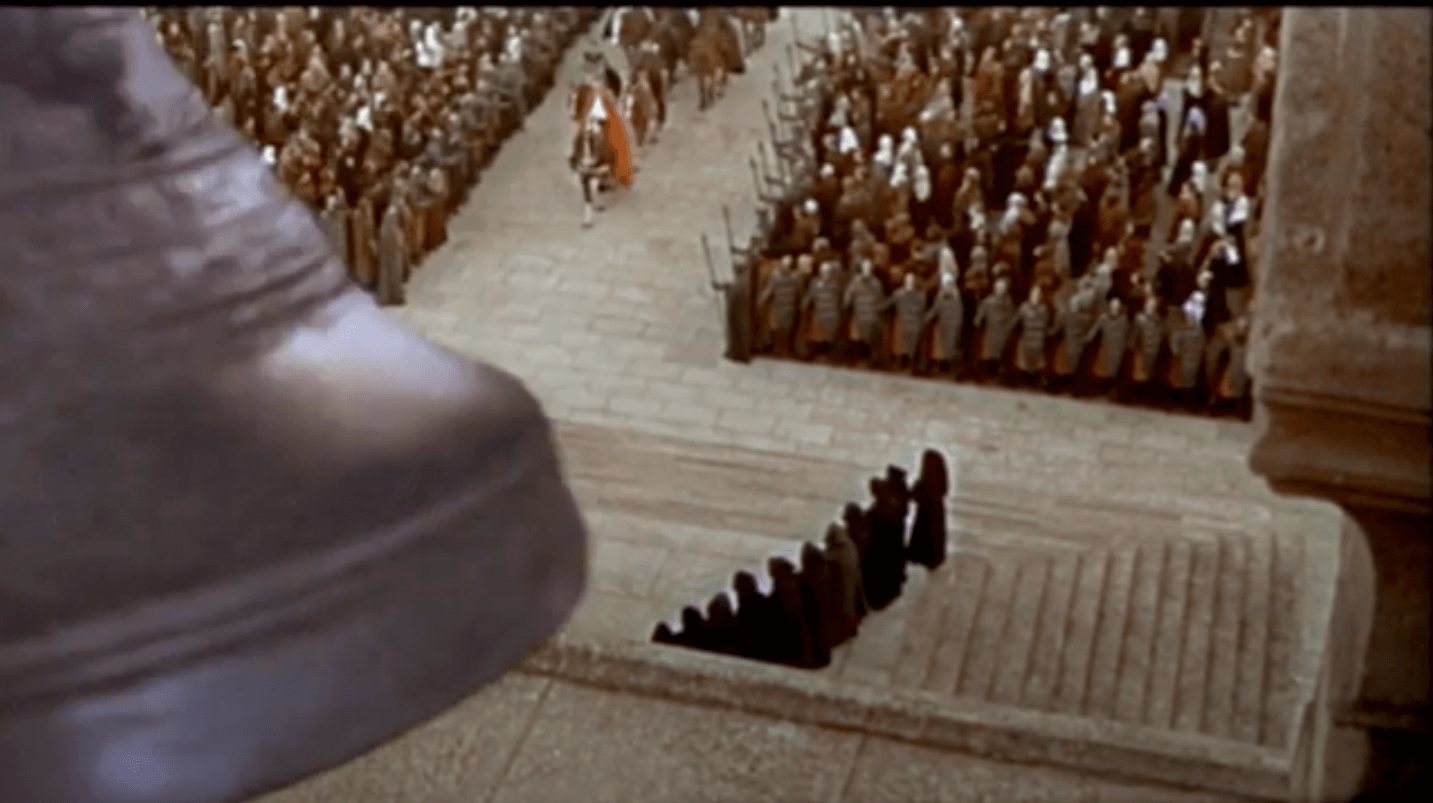

Cecil B. DeMille’s 1931 The Sign of the Cross was stripped of shots of bloody gladiatorial combat, and seminude girls menaced by crocodiles, and a gorilla.

The academy Award winner All Quiet on the Western Front suffered from the revisionism of the Breen Office. Too much emphasis on the horrors of war in popular culture might be detrimental to recruiting in time of war. In the 1934 re-release of All Quiet on the Western Front, this powerful moment amongst others was deleted: A soldier has grabbed the barbed wire to pull himself through, when an explosion fills the frame. When the dust clears only his hands remain still clinging to the wire.

Such sanitization of screen violence held until World War Two, when blood lust needed to be aroused for patriotic reasons. This justified the fudging of previous standards. Face wounds, previously forbidden, offered the wartime audience enhanced satisfaction at the death of the enemy. In Flying Tigers (1942) when Japanese pilots are struck by bullets, they clutch their faces with bloody fingers, or vomit blood. US pilots die cleanly.

Conversely, in Back to Bataan (1945), shots of brutality to US soldiers were intended to produce rage and reinforce in the audience the determination to achieve victory.

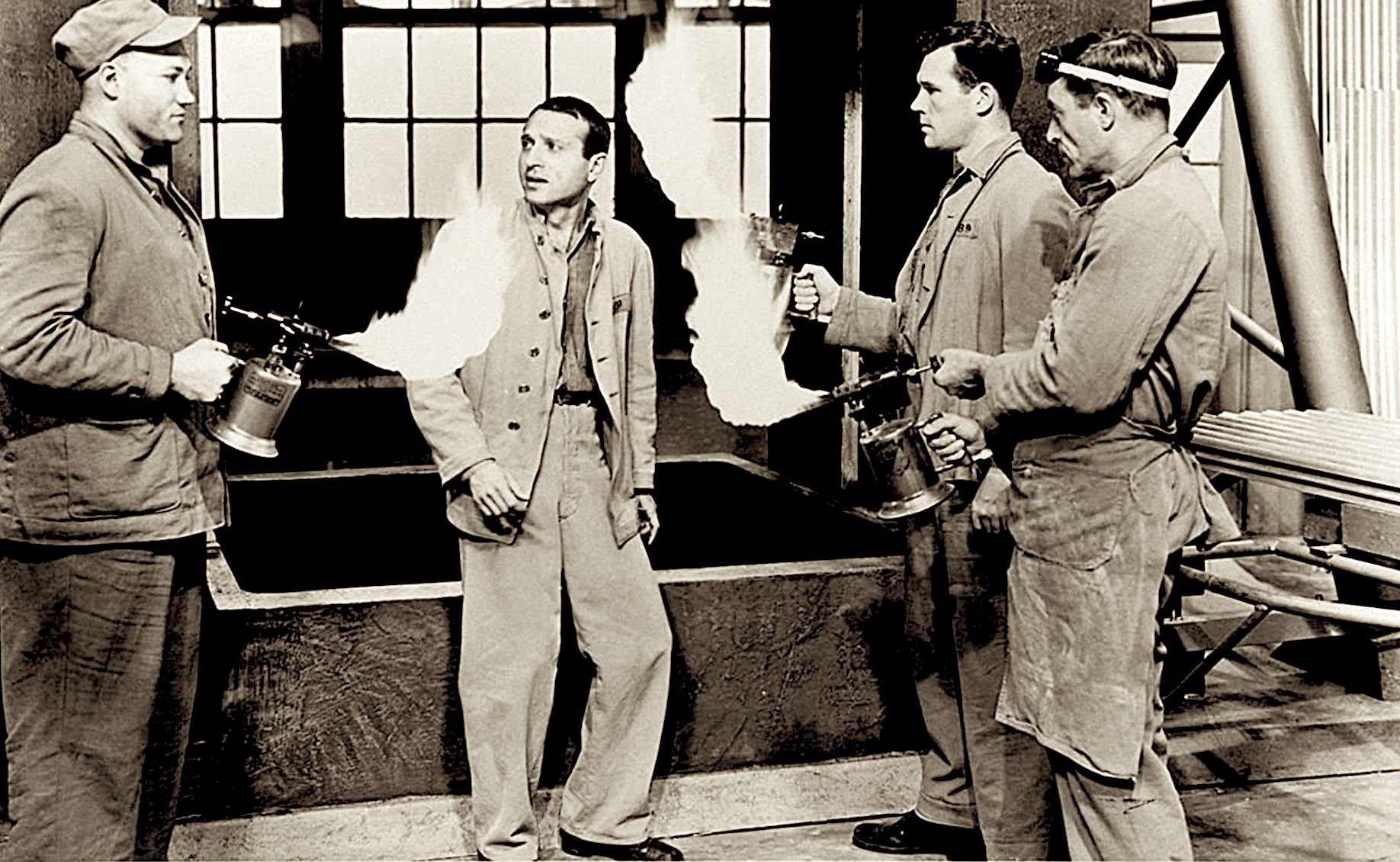

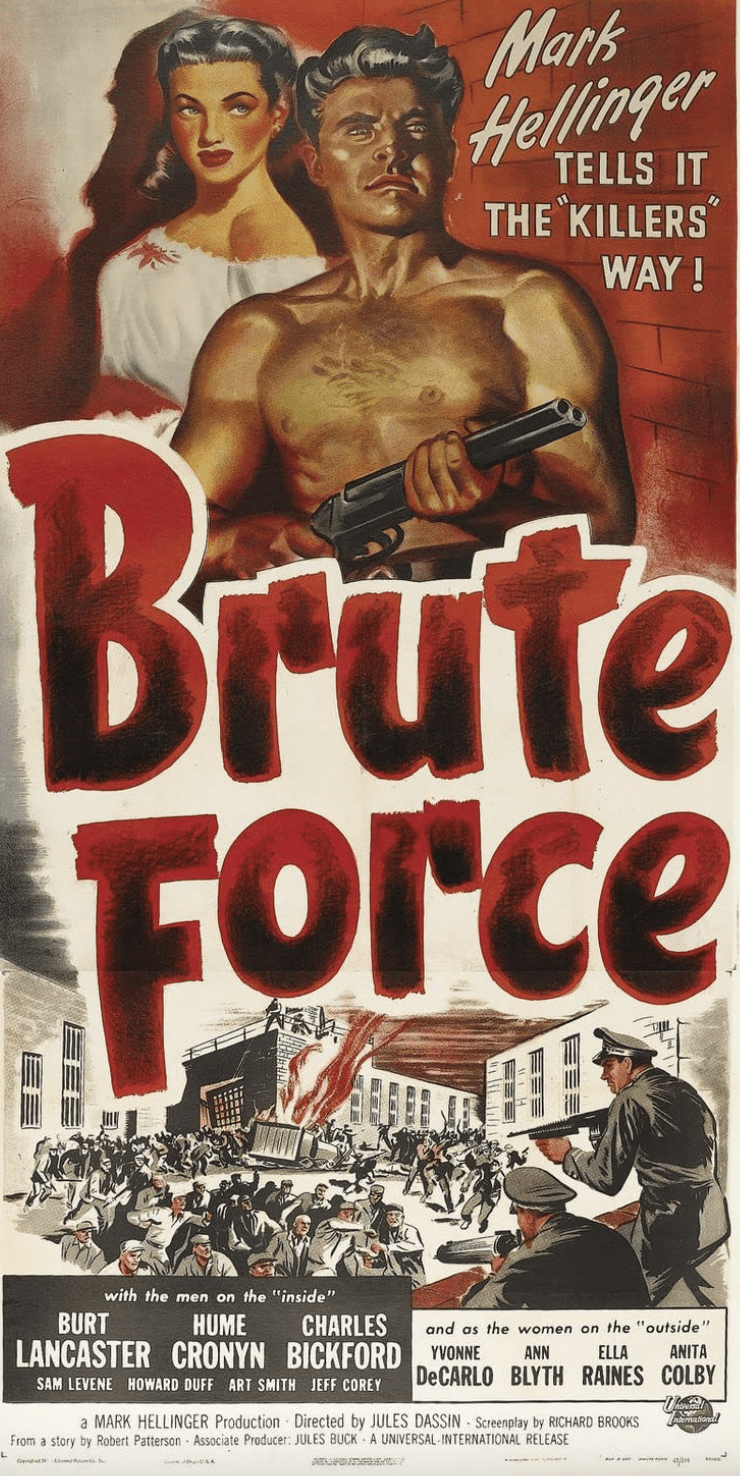

By 1945 the horrors of war experienced by a generation inevitably led to a gradual loosening of the PCA rules in the depiction of violence. The prison break movie Brute Force (1947), inspired by an actual two day riot at Alcatraz prison the year before, broke new ground in that genre. The film has a number of brutal scenes including the beating of a prisoner bound to a chair by straps, and the crushing of a stool pigeon prisoner under a stamping machine.

Critics at the time considered the climax of Brute Force displayed the most harrowing violence ever seen in movie theaters. The PCA was criticized for passing it, but justified the decision on the grounds that the prison conditions depicted would act as a deterrent to crime. By contrast, British censors considered the movie was detrimental to public perception of penal systems in general and by association British prisons. It was banned in the UK for several years. The eventual DVD release was rated suitable for age 12.

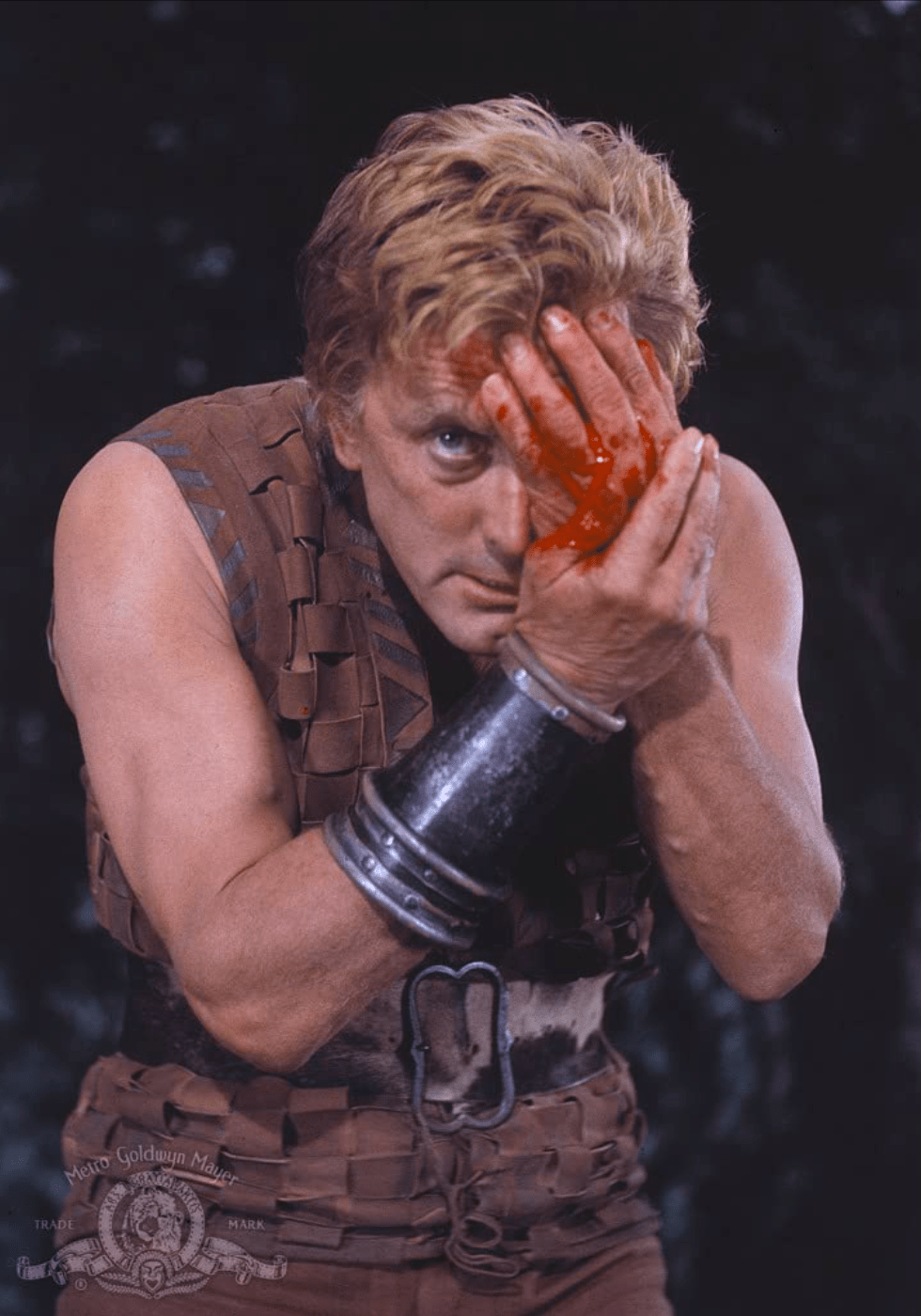

Technicolor blood, always more confronting than B&W blood, began to be seen again in historical subjects like Scaramouche (1952) Mel Ferrer bleeds politely from Stewart Granger’s blade.

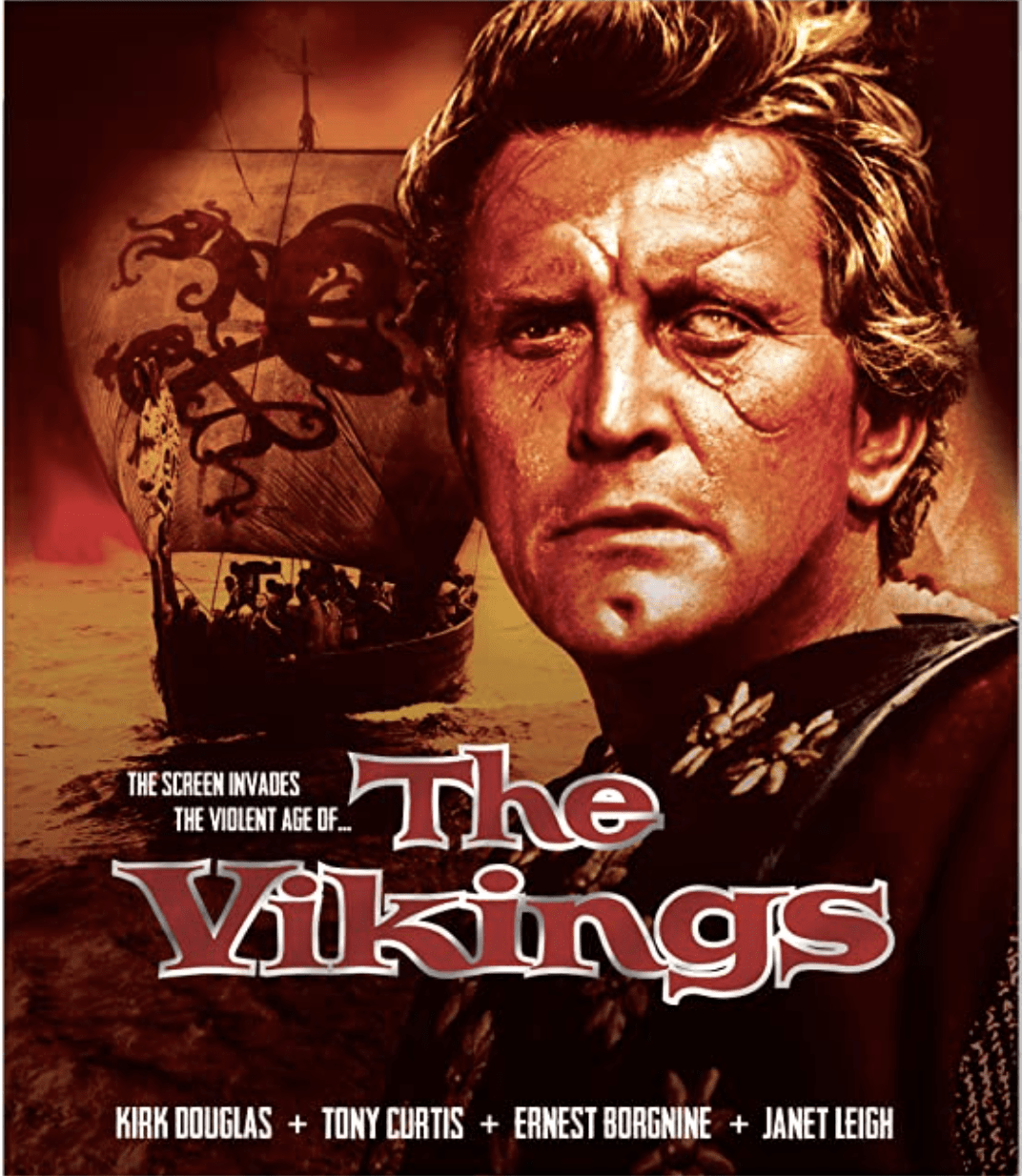

By 1958, Kirk Douglas could bleed less politely in his production of The Vikings.

To compete with television, movies had to deliver more grit than the US networks allowed. Bloodshed in westerns and big budget historical drama began to be given more leeway by the PCA. The same shots would not be permitted in a contemporary thriller; the censors’ rationale being that period costumes make violence less disturbing.

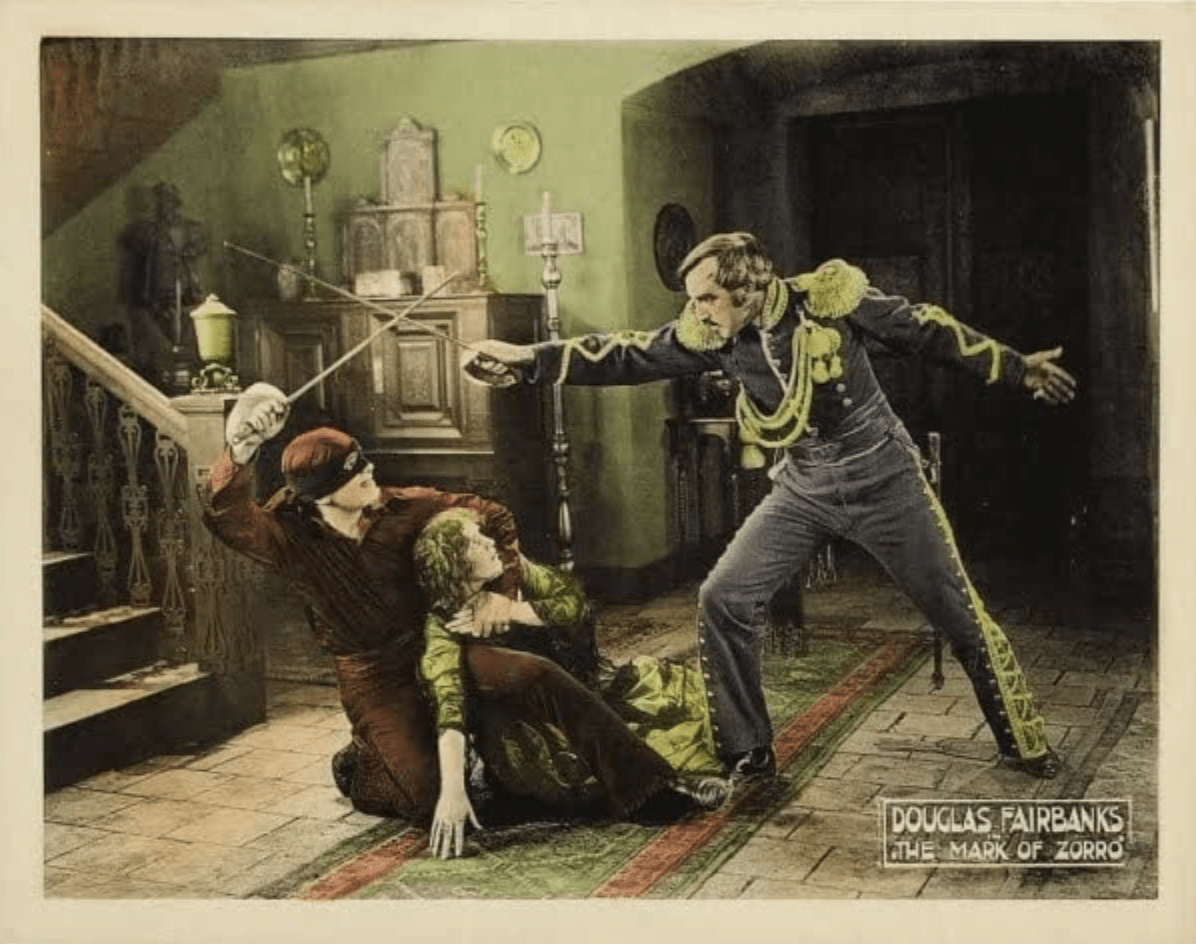

The BBFC were always more concerned with violence than their American counterparts. I began to notice multiple splice jumps during Italian Sword and Sandal epics that I enjoyed as a kid. One in particular was the Steve Reeves peplum epic, Giant of the Marathon (1960) to which to cinematographer / 2nd Unit director Mario Bava, soon to make a career in horror and giallo, contributed a stunning underwater battle as an homage to Douglas Fairbanks Snr.’s The Black Pirate. (1922) The BBFC was sensitive to penetration of the human body, and deleted several of Bava’s most impactful moments.

Arrow in the eyeball was a guaranteed Yikes! moment for the fans. Bava used it again in Goliath Against The Vampires (1961).

This time the BBFC let it through, but gave the film an “X” Certificate, a real rarity for peplum. When fire was combined with penetration by arrow or spear, it amplified the sense of pain.

The BBFC saw it as gratuitous sadistic detail and such shots were cut to obtain a ‘U’ Certificate for unrestricted exhibition.

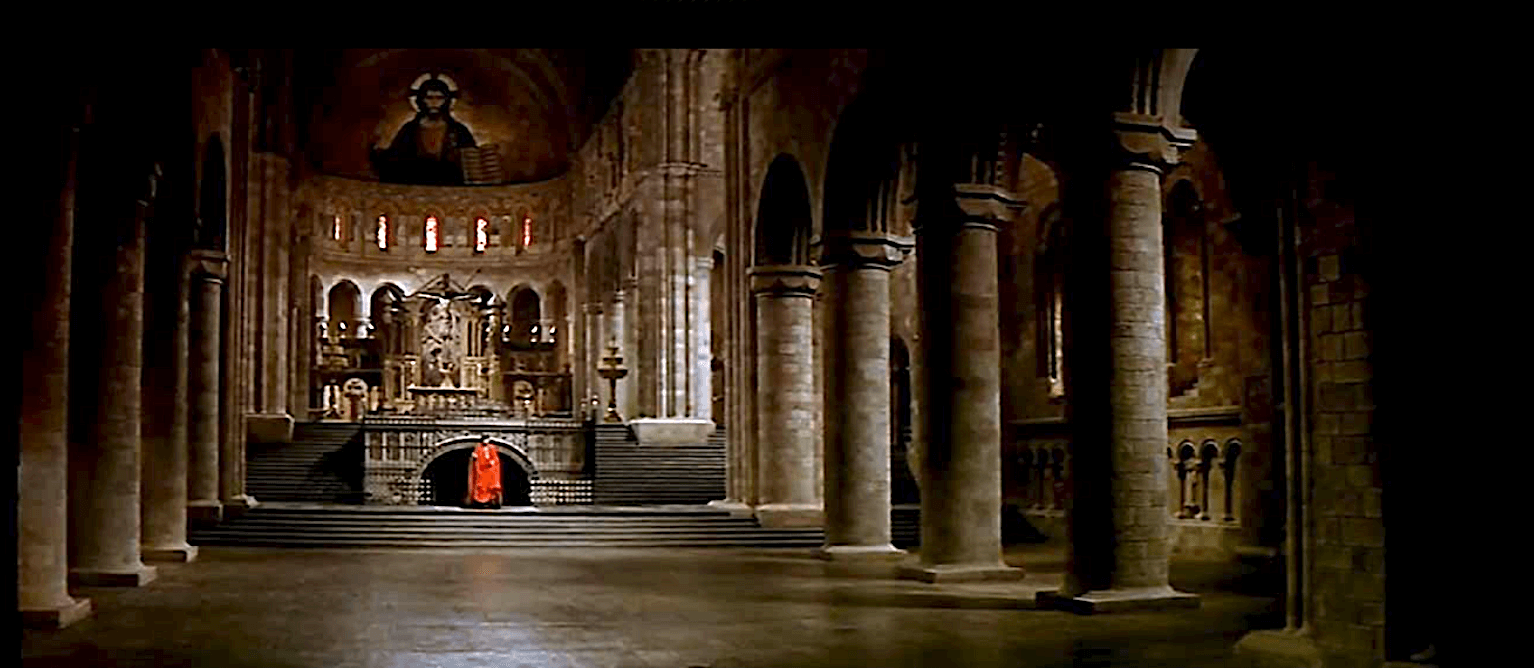

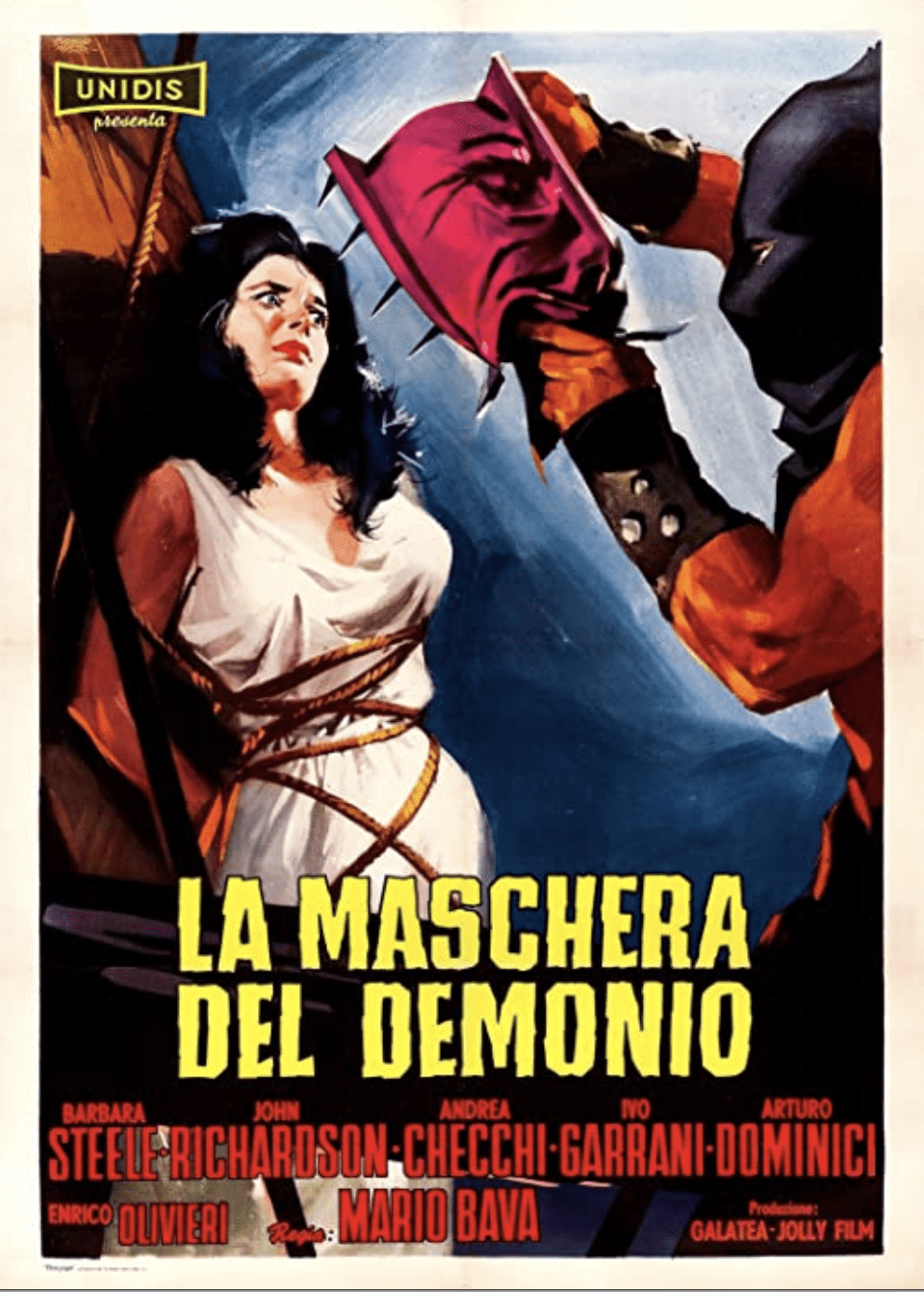

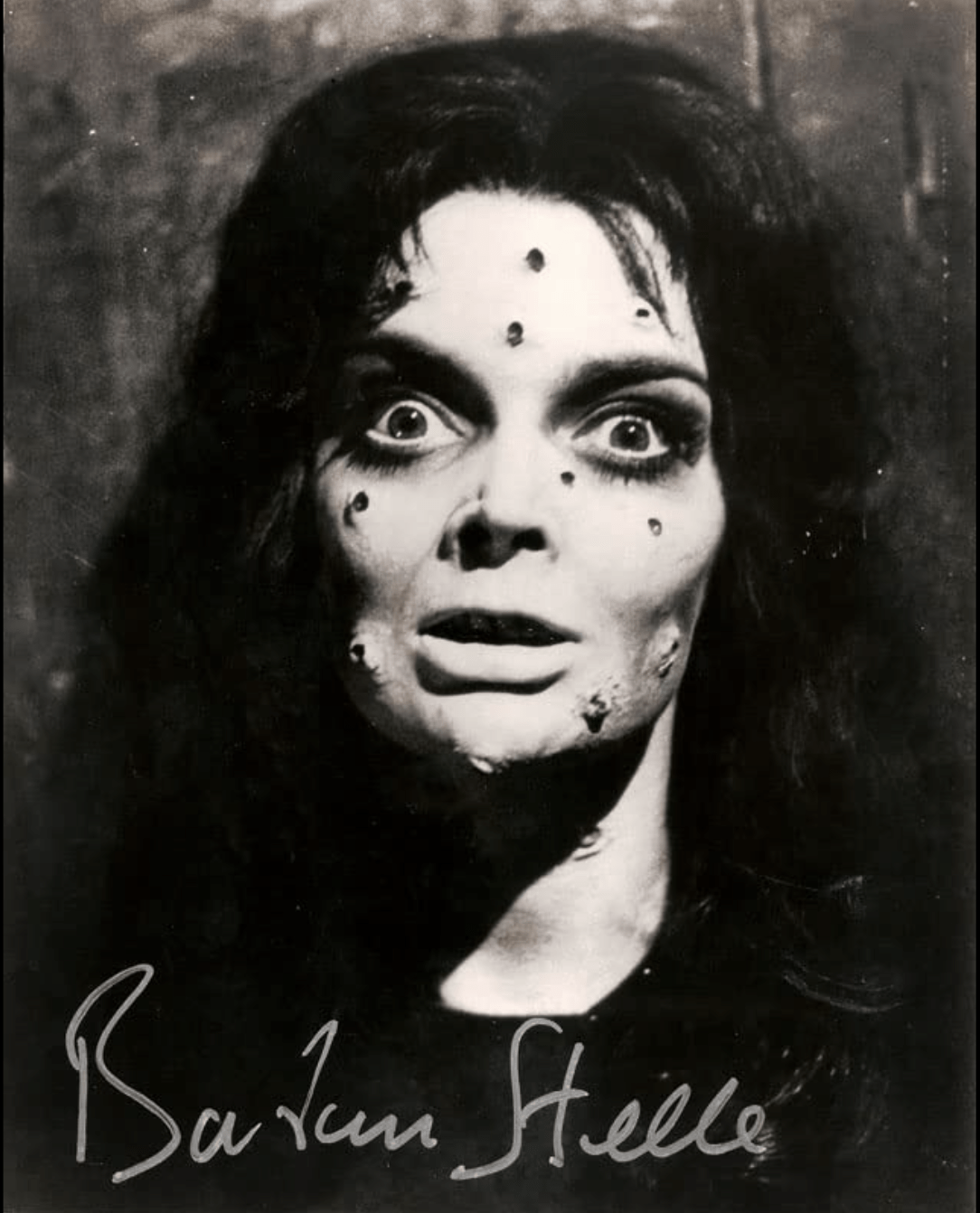

British audiences were denied Mario Bava’s stunning 1960 directorial debut Black Sunday.

This gothic masterpiece remained banned by the BBFC for 8 years, then released pruned of its best disturbing images. Nonetheless it made a star out of little known British actress Barbara Steele. The full uncut version was not released till 1992.

UK’s Hammer Films advanced the boundaries of horror at a time when the British film industry was ailing, as the BBFC, a quasi- autonomous government instrumentality, was quite aware. They knew that for Hammer’s color remakes of black and white horror classics Dracula, Frankenstein and The Mummy to prosper in the American market, they had to loosen previous restrictions on blood and dismemberment in the new “X” Certificate. Not as much as Hammer wanted of course, but it worked.

Naturally, there was a backlash from religious groups, but Hammer’s strong box office performance proved the public were ready. The Dracula/Frankenstein/ Mummy franchises were a huge success world wide, which in turn attracted production back to the UK. The BBFCs policy liberalization of Adults Only movies had an impact that benefitted trade.

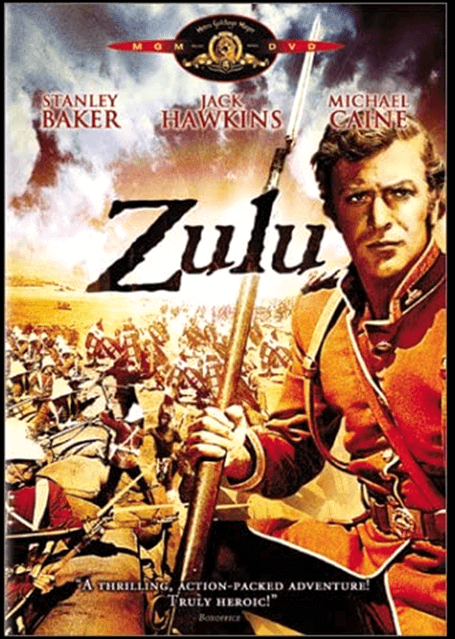

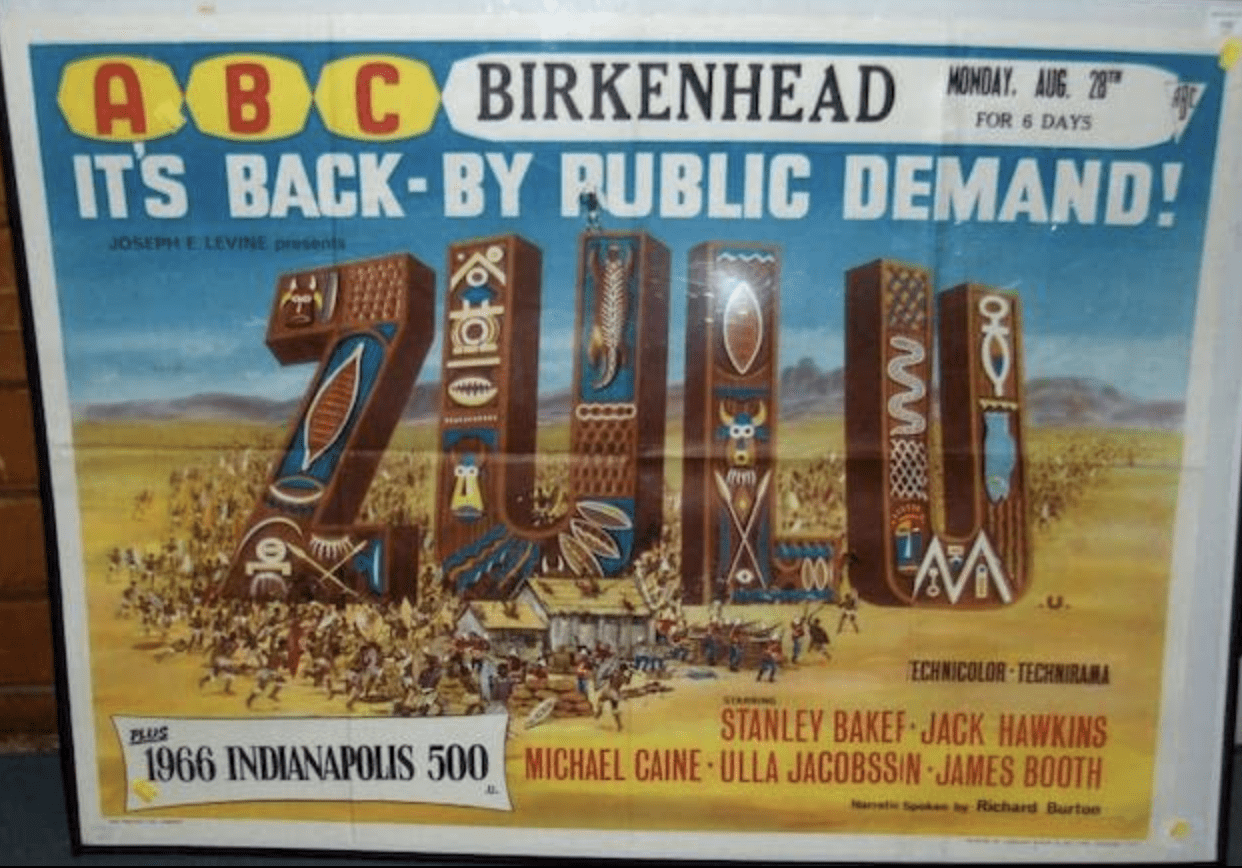

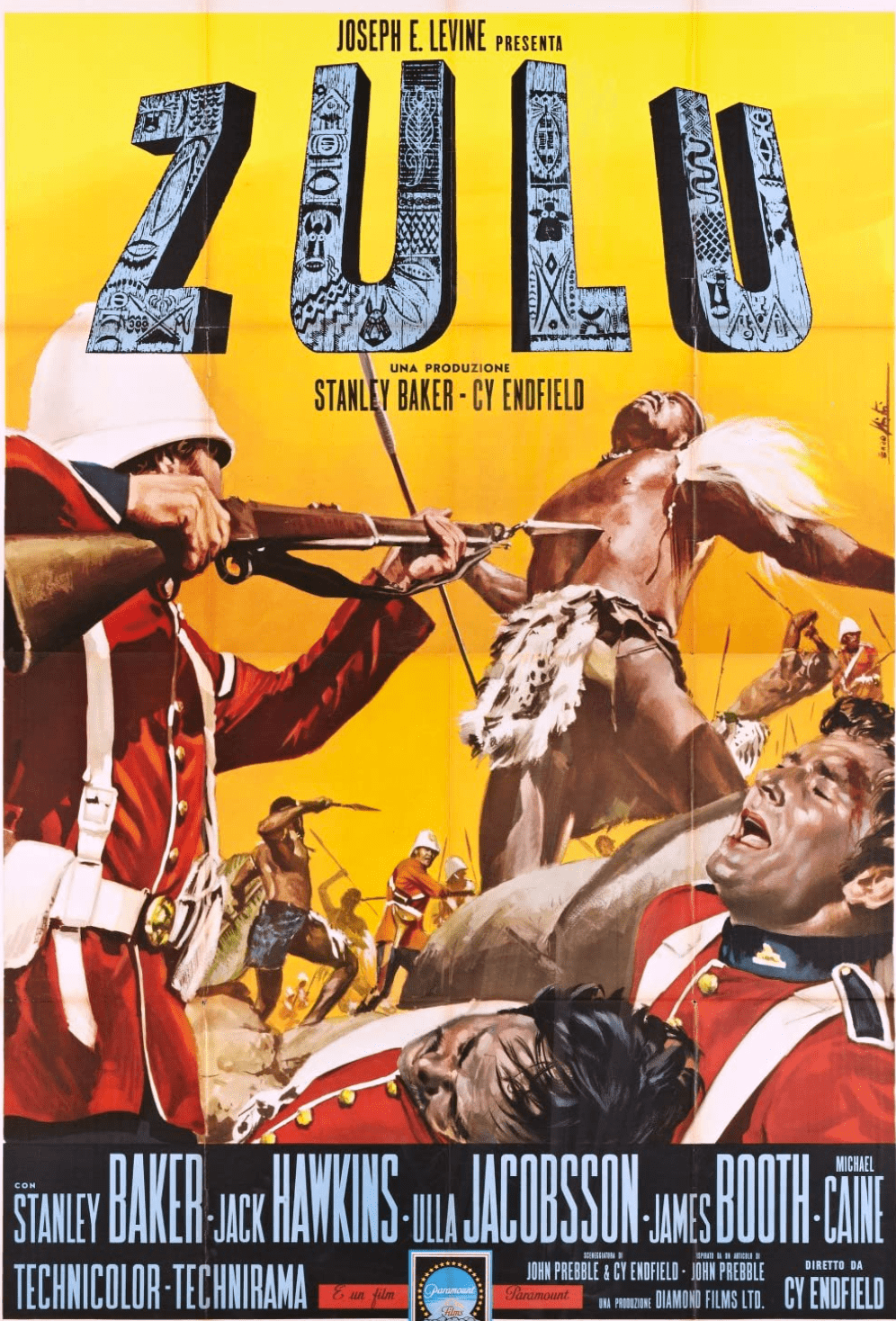

I credit American director Cy Raker Endfield’s ZULU with finally pushing the boundaries of the British “U” Certificate (all audiences admitted) in 1964. I saw it on its first weekend. There was a distinct intake of breath from across a packed house when, early in the movie, hundreds of bare breasted Zulu girls began a ritual dance.

Topless girls were normally verboten in a “U”Certificate film, ZULU’s requested classification. However there was one category of footage permitted for all audiences by the BBFC since the silent era – actual footage of traditional native ceremonies even if the participants are unclothed. Newsreels and short subjects containing such material were considered a valuable natural history record and permitted for public exhibition. Endfield claimed that that the sequence he filmed was an authentic Zulu mass wedding ceremony, that would provide cultural context to the Zulu side of the story. In 1961, the spurious feature documentary on nudism clubs – Naked as Nature Intended – had received an “A” Certificate after cuts. There was no precedent for anything less than an “A” for bare breasts, when ZULU came before the BBFC. Also there was an “A” Certificate level of blood and violence by prevailing standards.  The BBFC were aware of the financial implications, if the expensive 70mm. British production did not receive a “U” Certificate for its release in the UK’s prime summer holiday playing time, potentially the patriotic ZULU‘s most lucrative market. Box office statistics suggested generally “A” films earned 20% less than comparable “U” films. Some minor cuts in spear and bayonet wounds were made, and the needed “U”Certificate was obtained. Occasionally market forces influence a censors’ decision. In a good way. The British Film Institute Monthly Bulletin review questioned the wisdom of the BBFC’s “U” Certificate, suggesting ZULU was ” too tough and bloody” for younger audiences.

The BBFC were aware of the financial implications, if the expensive 70mm. British production did not receive a “U” Certificate for its release in the UK’s prime summer holiday playing time, potentially the patriotic ZULU‘s most lucrative market. Box office statistics suggested generally “A” films earned 20% less than comparable “U” films. Some minor cuts in spear and bayonet wounds were made, and the needed “U”Certificate was obtained. Occasionally market forces influence a censors’ decision. In a good way. The British Film Institute Monthly Bulletin review questioned the wisdom of the BBFC’s “U” Certificate, suggesting ZULU was ” too tough and bloody” for younger audiences.

As the sixties progressed, and the control exerted by the PCA came to an end, explicit violence in American movies gradually increased across all genres. Film makers were anxious to try out advances in prosthetic make up technology. Multiple blood squibs in slow-motion would finally reach the screen in 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde.

A year later Sam Peckinpah took the bullet ballet to a new level. For a while, blood squibs became the action director’s new toy. More about how censorship evolved through the 1970’s & 80’s in a future post.

Throughout the decades of censorship under the dominant bodies of the PCA & BBFC, many film makers have tussled with the censors over violence, nudity, and taboo subject matter. None battled them so consistently over a 50 year period than Alfred Hitchcock. His chess games with the censors on both sides of the Atlantic will feature in the next chapter. HITCHCOCK: CENSORSHIP SABOTEUR!

But let’s go back to the beginning.

But let’s go back to the beginning. They provided most of the photographic materials in this article. And to whet your appetite, Jonas Nordin has created

They provided most of the photographic materials in this article. And to whet your appetite, Jonas Nordin has created

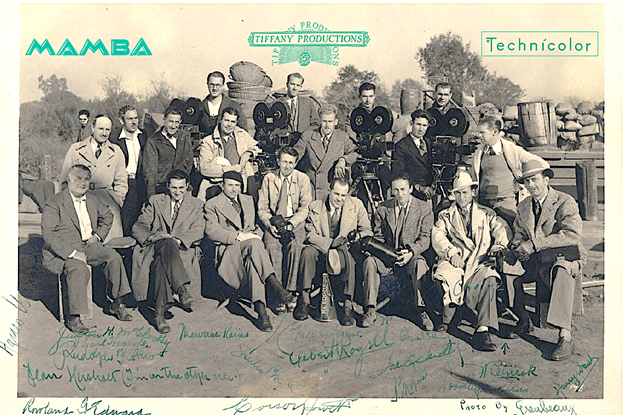

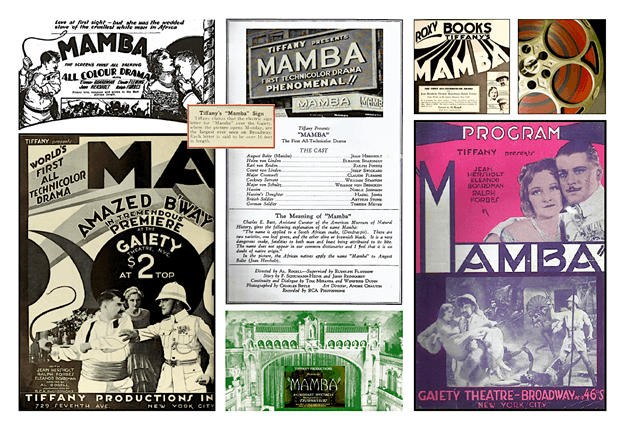

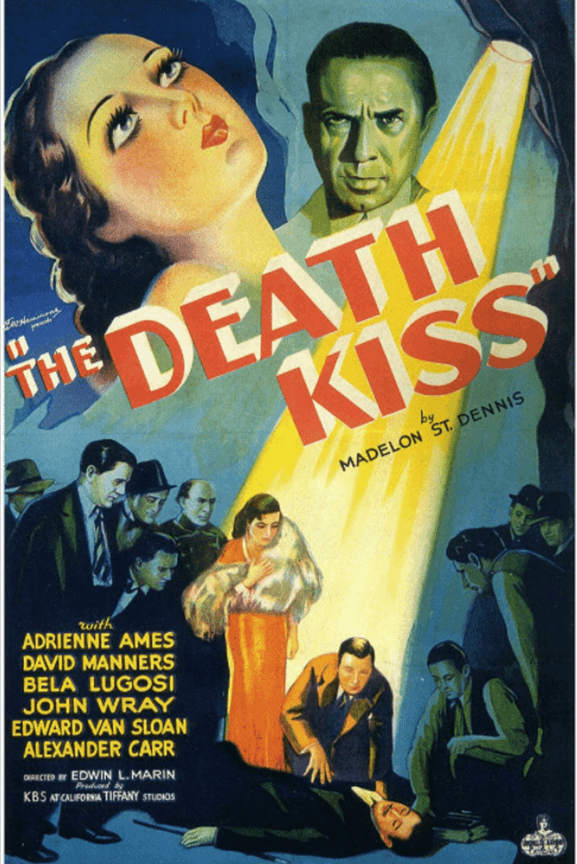

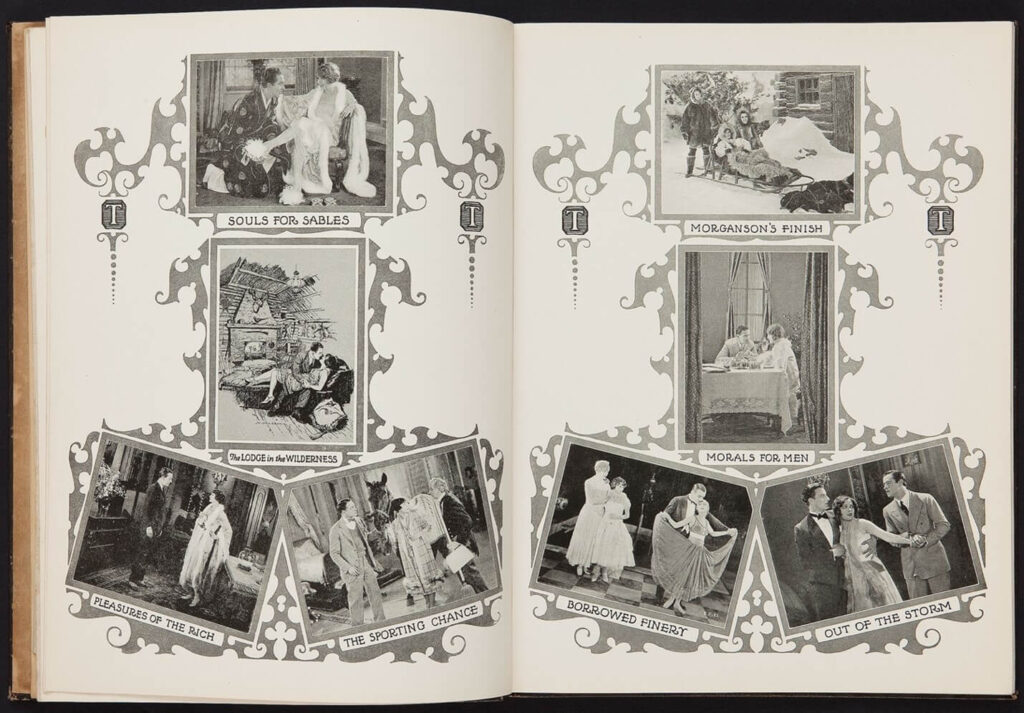

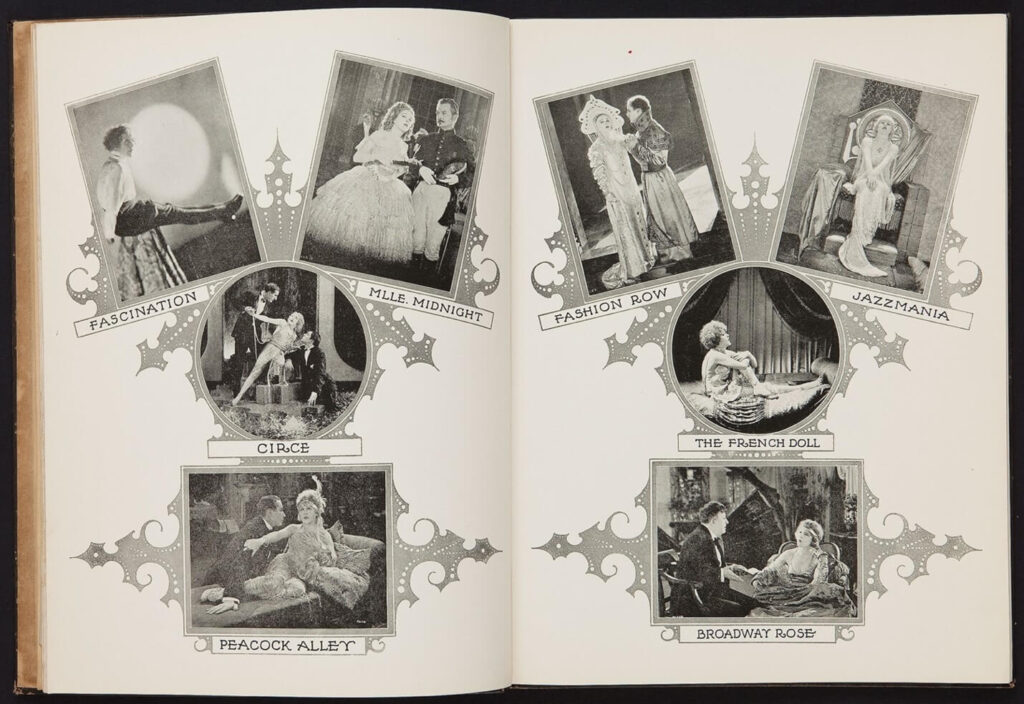

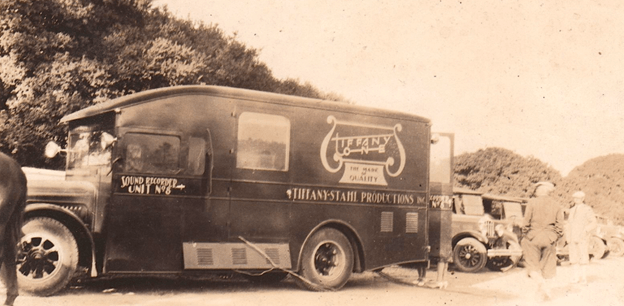

MAMBA was made by Tiffany Productions. To give broader context to Tiffany’s most notable movie, I’ll chart the 14 year history of the company’s rise and fall. There will be occasional digressions into evolving technology and industry practice to provide a sense of the era. Think of it as the short subject that precedes the main attraction.

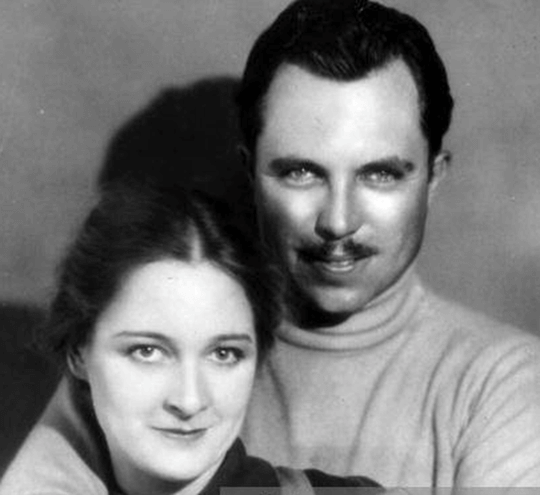

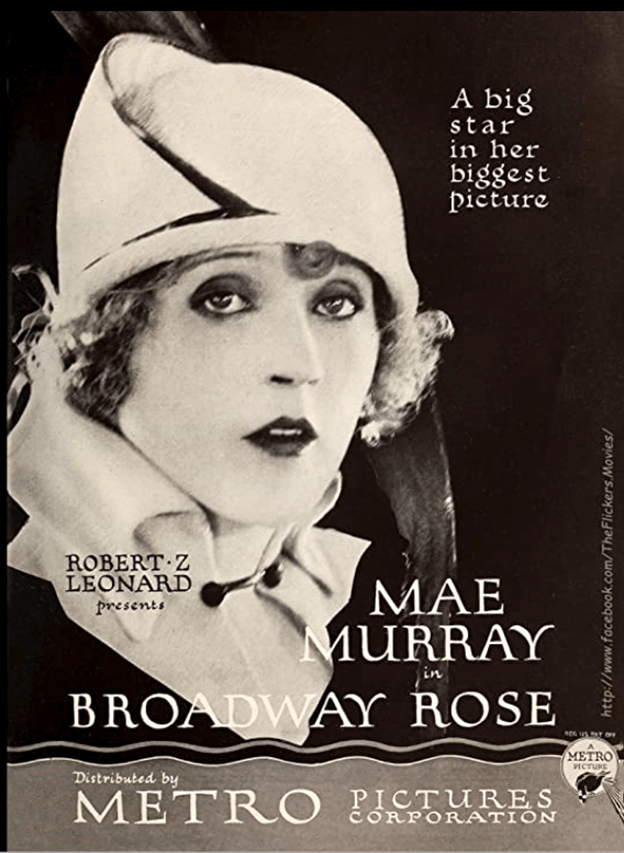

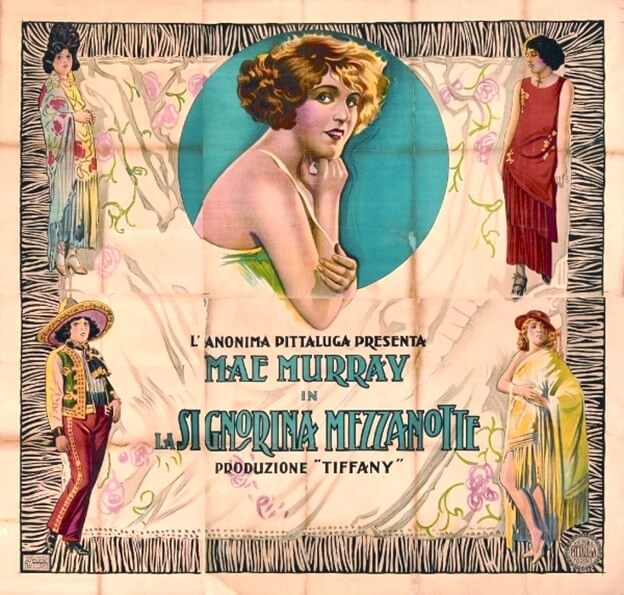

MAMBA was made by Tiffany Productions. To give broader context to Tiffany’s most notable movie, I’ll chart the 14 year history of the company’s rise and fall. There will be occasional digressions into evolving technology and industry practice to provide a sense of the era. Think of it as the short subject that precedes the main attraction. Similarly, Tiffany’s purpose was to produce vehicles for its star Mae Murray, directed by her husband Robert Leonard, releasing them through rising distributor Metro to the nickelodeons of America. Leonard & Mae, the founders of Tiffany Productions, had sadly different career paths that are a window into the twists and turns of Silent Hollywood success stories.

Similarly, Tiffany’s purpose was to produce vehicles for its star Mae Murray, directed by her husband Robert Leonard, releasing them through rising distributor Metro to the nickelodeons of America. Leonard & Mae, the founders of Tiffany Productions, had sadly different career paths that are a window into the twists and turns of Silent Hollywood success stories.

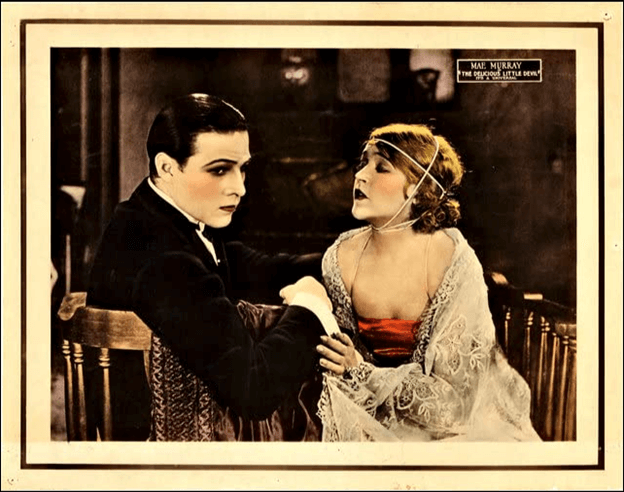

A contract at Universal followed, where he became chiefly associated with the films of his future wife, the ex-Ziegfeld Follies star Mae Murray.

A contract at Universal followed, where he became chiefly associated with the films of his future wife, the ex-Ziegfeld Follies star Mae Murray. Mae Murray, a striking beauty at 5’ 2”, with frizzy blonde hair, was born Marie Adrienne Koenig in 1885. In 1908, she joined the chorus line of the Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway and with determination and political skill beat out the competition to achieve headliner status by 1915. Her motion picture debut in To Have And To Hold a year later made her a major star for Universal. Roles opposite Rudolph Valentino in The Delicious Little Devil and Big Little Person followed.

Mae Murray, a striking beauty at 5’ 2”, with frizzy blonde hair, was born Marie Adrienne Koenig in 1885. In 1908, she joined the chorus line of the Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway and with determination and political skill beat out the competition to achieve headliner status by 1915. Her motion picture debut in To Have And To Hold a year later made her a major star for Universal. Roles opposite Rudolph Valentino in The Delicious Little Devil and Big Little Person followed.

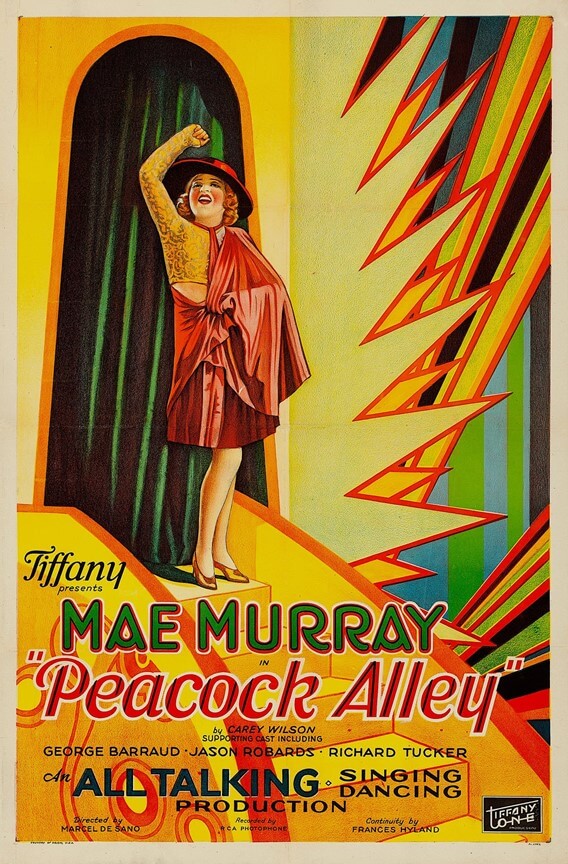

Salary, in addition to profit share, for her 1922 hit Peacock Alley was $10,000 a week. She became known as “The Girl with the Bee-Stung Lips” and “The Gardenia of the Screen”. For a brief period she even wrote a weekly column for newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Critics sniped at her over-the-top costumes and exaggerated emoting, but the eight movies Tiffany Productions delivered to Metro were popular and financially successful.

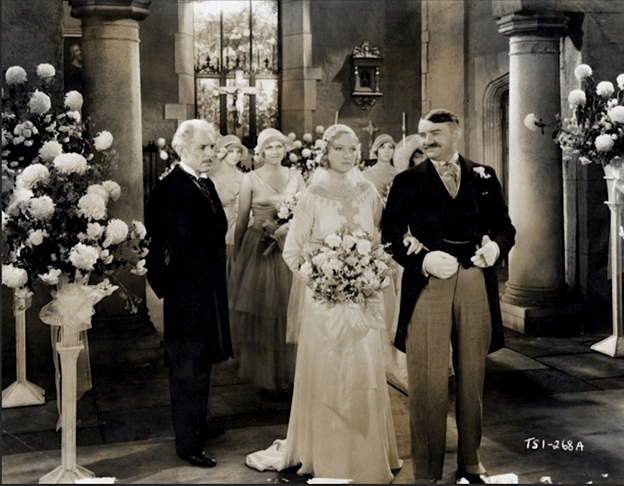

Salary, in addition to profit share, for her 1922 hit Peacock Alley was $10,000 a week. She became known as “The Girl with the Bee-Stung Lips” and “The Gardenia of the Screen”. For a brief period she even wrote a weekly column for newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Critics sniped at her over-the-top costumes and exaggerated emoting, but the eight movies Tiffany Productions delivered to Metro were popular and financially successful. Perhaps Mae Murray’s volatile personality became too much for Leonard and the couple divorced in 1925. Their lives diverged down sadly different paths. At that time three rival distributors, Metro, Goldwyn, and Mayer merged into a new powerhouse – MGM. Robert Z Leonard left Tiffany, joined MGM. An enduring marriage to another actress soon followed. Leonard was perfect for the new studio system, turning out musicals and light comedies, with occasional big hits like The Great Zeigfeld, which won the Best Picture Oscar in 1936, and a lavish 1940 version of Pride and Prejudice, starring Laurence Olivier, written (curiously) by Aldous Huxley. Leonard became one of the studio’s most reliable contract directors till his retirement in 1955. Fate was not so kind to his ex-wife Mae Murray, seen her with 4th husband European Prince David Mdvani.

Perhaps Mae Murray’s volatile personality became too much for Leonard and the couple divorced in 1925. Their lives diverged down sadly different paths. At that time three rival distributors, Metro, Goldwyn, and Mayer merged into a new powerhouse – MGM. Robert Z Leonard left Tiffany, joined MGM. An enduring marriage to another actress soon followed. Leonard was perfect for the new studio system, turning out musicals and light comedies, with occasional big hits like The Great Zeigfeld, which won the Best Picture Oscar in 1936, and a lavish 1940 version of Pride and Prejudice, starring Laurence Olivier, written (curiously) by Aldous Huxley. Leonard became one of the studio’s most reliable contract directors till his retirement in 1955. Fate was not so kind to his ex-wife Mae Murray, seen her with 4th husband European Prince David Mdvani. Murray clashed with MGM chief Louis B Mayer, then, at the advice of Mdvani, whom she had appointed her new manager, she broke her contract. Later she would plead to return but Mayer refused. His enmity discouraged many directors from considering her. The dawn of the sound era was another blow.

Murray clashed with MGM chief Louis B Mayer, then, at the advice of Mdvani, whom she had appointed her new manager, she broke her contract. Later she would plead to return but Mayer refused. His enmity discouraged many directors from considering her. The dawn of the sound era was another blow. Her first talkie Peacock Alley in 1930, a remake of her 1921 silent hit, revealed she had little flair for dialogue. It flopped, as did her two subsequent releases. She sued Tiffany for destroying her career and lost. Her husband/ manager Mdvani – how predictable – drained most of her wealth before their divorce.

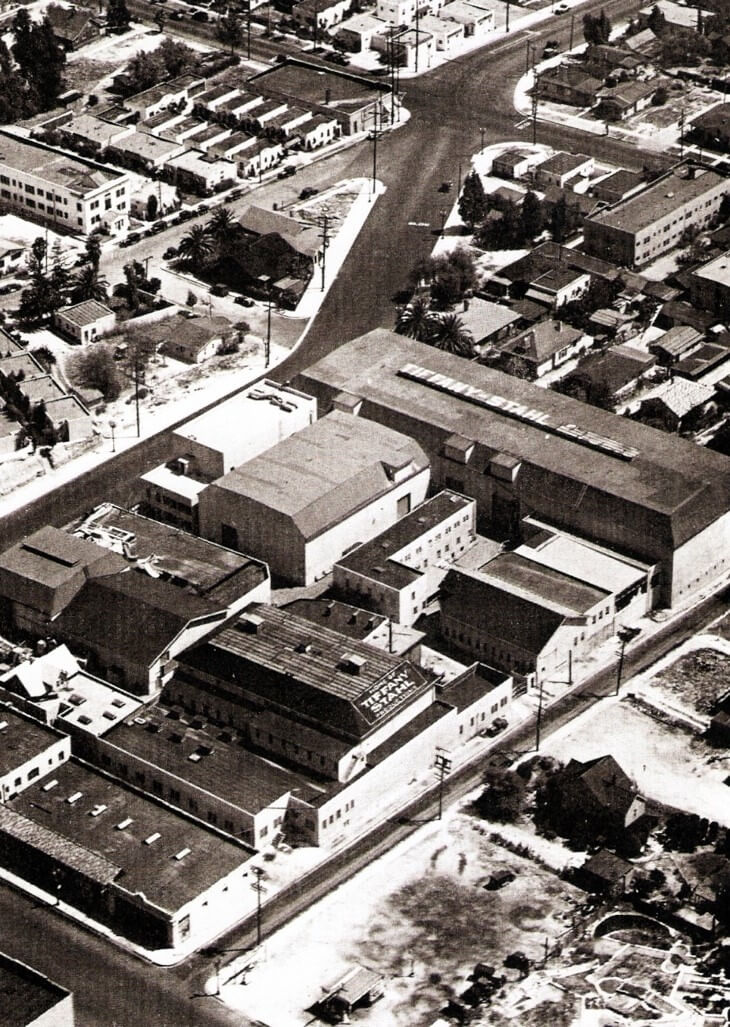

Her first talkie Peacock Alley in 1930, a remake of her 1921 silent hit, revealed she had little flair for dialogue. It flopped, as did her two subsequent releases. She sued Tiffany for destroying her career and lost. Her husband/ manager Mdvani – how predictable – drained most of her wealth before their divorce. The man to do the job was producer director John Stahl, who was recruited, after the Leonard/Murray divorce, to be the new CEO. Along with executives Phil Goldstone and Maurice H Hoffman, he retooled the company for low budget production to generate cash flow. Tiffany has been called a Poverty Row studio, in the vernacular of the time, one whose films had lower budgets, lesser stars, if stars at all, and much lower production values than major studios. In fact Tiffany was more an independent production/distribution company with its own studio, having acquired the old Reliance / Majestic backlot on Sunset Boulevard.

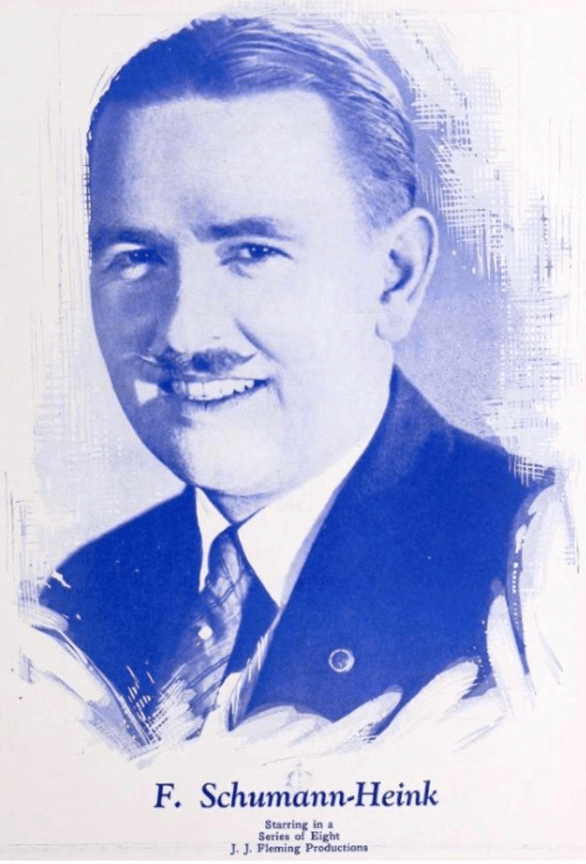

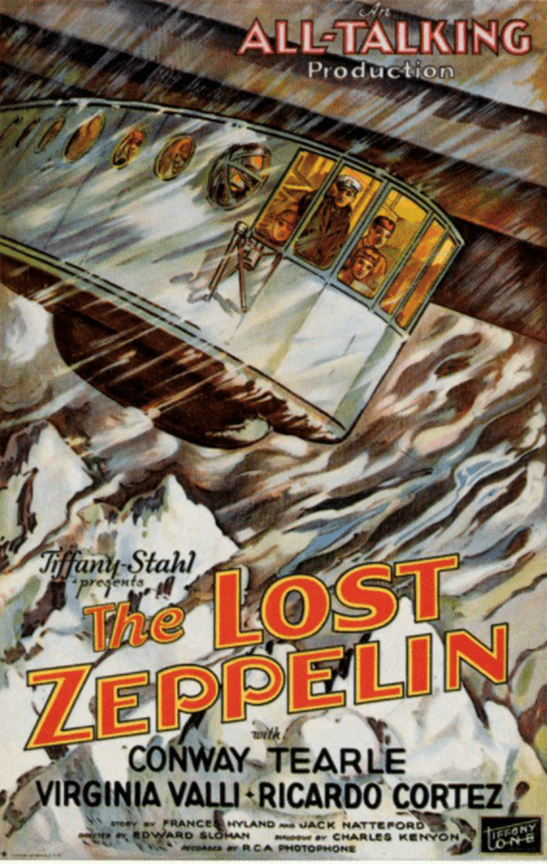

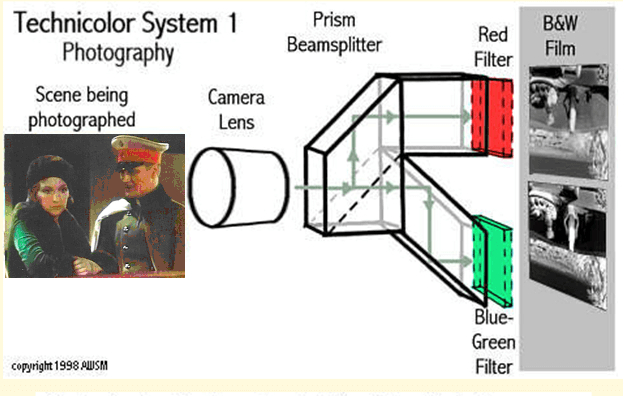

The man to do the job was producer director John Stahl, who was recruited, after the Leonard/Murray divorce, to be the new CEO. Along with executives Phil Goldstone and Maurice H Hoffman, he retooled the company for low budget production to generate cash flow. Tiffany has been called a Poverty Row studio, in the vernacular of the time, one whose films had lower budgets, lesser stars, if stars at all, and much lower production values than major studios. In fact Tiffany was more an independent production/distribution company with its own studio, having acquired the old Reliance / Majestic backlot on Sunset Boulevard. Stahl renamed the company Tiffany-Stahl Productions and released 70 features, both silent and sound, 20 of which were Westerns. The new Tiffany invested in developing technologies to get ahead of the competition. They commissioned shorts subjects, photographed in a breakthrough color process known as Technicolor. The iconic Technicolor brand has a fascinating history and you can get into the weeds of it at

Stahl renamed the company Tiffany-Stahl Productions and released 70 features, both silent and sound, 20 of which were Westerns. The new Tiffany invested in developing technologies to get ahead of the competition. They commissioned shorts subjects, photographed in a breakthrough color process known as Technicolor. The iconic Technicolor brand has a fascinating history and you can get into the weeds of it at  Your eyes may glaze as the differences between 2-Strip and 3-Strip Technicolor are explained, but it’s worth the study, because it demonstrates the ingenuity of the early camera pioneers; how fraught with mechanical and chemical complexities the process of creating a color image was. Today, just hit record on your phone.

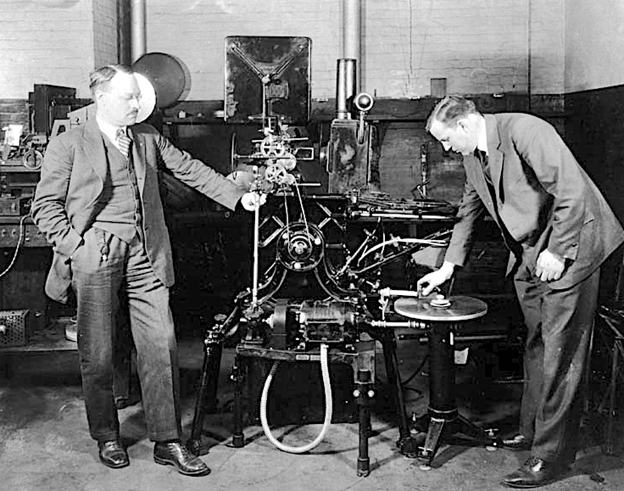

Your eyes may glaze as the differences between 2-Strip and 3-Strip Technicolor are explained, but it’s worth the study, because it demonstrates the ingenuity of the early camera pioneers; how fraught with mechanical and chemical complexities the process of creating a color image was. Today, just hit record on your phone. The huge demand for sound movies in 1927 enabled Stahl and his team to make a lucrative deal with RCA: If a cinema owner agreed to book a block of 26 Tiffany films, RCA would install the sound gear at a bargain rate. In the early days of this technology, sound came from a Gramophone disc played like a Gramophone record in synch with the picture. As many as 2,460 theaters signed up for the deal, providing Tiffany with a guaranteed distribution network.

The huge demand for sound movies in 1927 enabled Stahl and his team to make a lucrative deal with RCA: If a cinema owner agreed to book a block of 26 Tiffany films, RCA would install the sound gear at a bargain rate. In the early days of this technology, sound came from a Gramophone disc played like a Gramophone record in synch with the picture. As many as 2,460 theaters signed up for the deal, providing Tiffany with a guaranteed distribution network.

For an understanding of the difficulties of early sound technology, the Vitaphone Wikipedia website is illuminating. Vitaphone was vulnerable to severe synchronization problems, famously spoofed in MGM’s 1952 musical about the Silent Era’s transition into Sound – Singin’ in the Rain. If a record was improperly cued up or bumped, the sound would stray out of sync with the picture, and the projectionist would have to try to manually acquire sync. The problem disappeared within a few years when soundtracks were printed in synch with the image on the 35mm film itself.

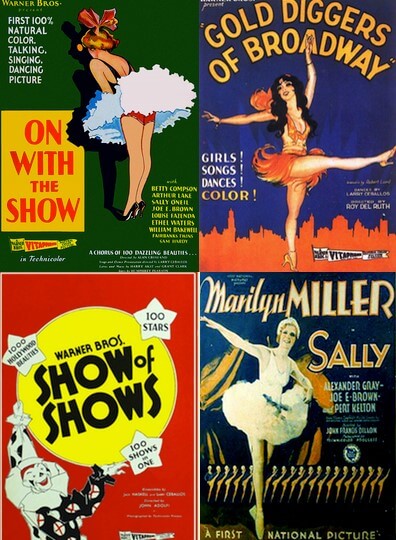

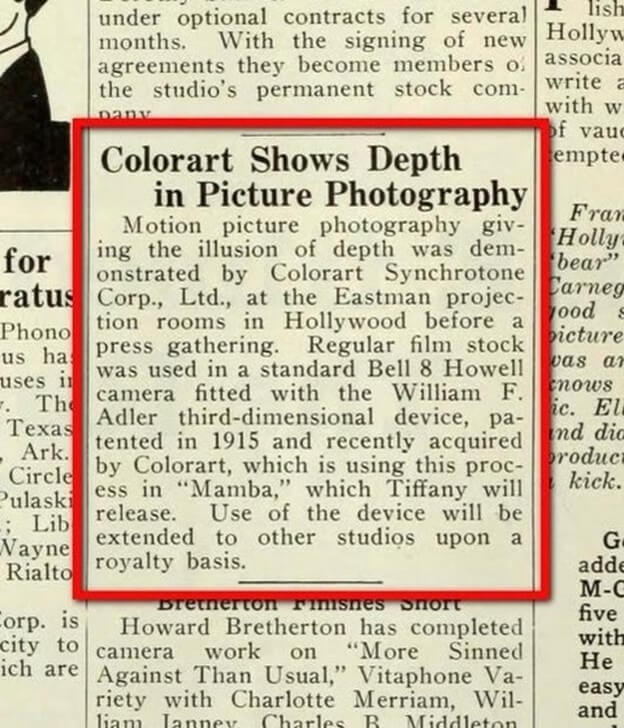

For an understanding of the difficulties of early sound technology, the Vitaphone Wikipedia website is illuminating. Vitaphone was vulnerable to severe synchronization problems, famously spoofed in MGM’s 1952 musical about the Silent Era’s transition into Sound – Singin’ in the Rain. If a record was improperly cued up or bumped, the sound would stray out of sync with the picture, and the projectionist would have to try to manually acquire sync. The problem disappeared within a few years when soundtracks were printed in synch with the image on the 35mm film itself. As sound movies swept the silent off the screen, Stahl felt ready to take on the next technological milestone: a full-length sound feature in Technicolor. The major studios had all rushed spectacular Technicolor musicals into production on their new sound stages, tying up almost all Technicolor’s twelve cameras. To jump ahead of the competition, Tiffany decided to make the world’s first outdoor spectacular in color and 3D.

As sound movies swept the silent off the screen, Stahl felt ready to take on the next technological milestone: a full-length sound feature in Technicolor. The major studios had all rushed spectacular Technicolor musicals into production on their new sound stages, tying up almost all Technicolor’s twelve cameras. To jump ahead of the competition, Tiffany decided to make the world’s first outdoor spectacular in color and 3D. However there is no record of Mamba being shown in 3D. They had to get the movie into theaters fast, and there was no time to perfect the process.

However there is no record of Mamba being shown in 3D. They had to get the movie into theaters fast, and there was no time to perfect the process.

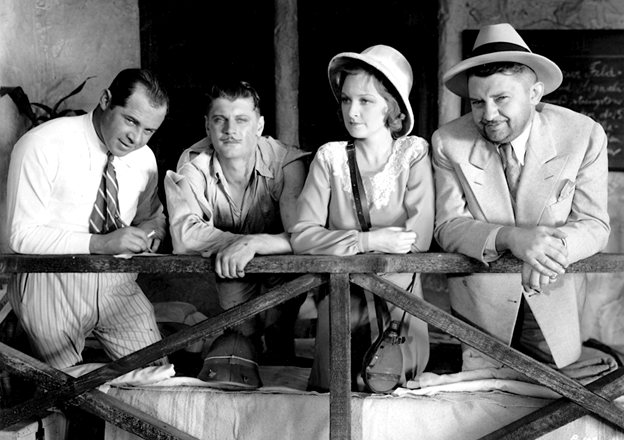

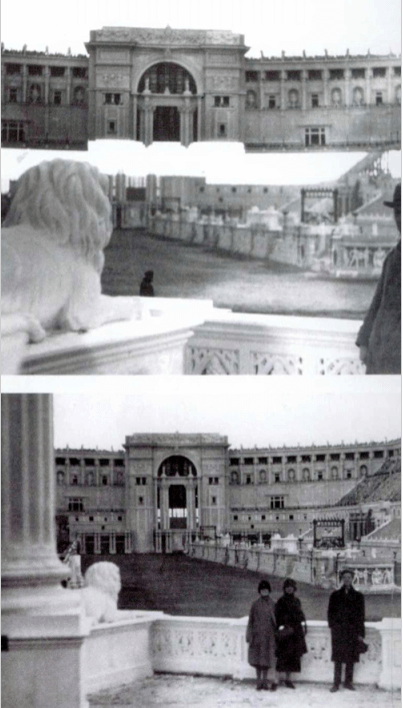

Mamba was shot in approximately 10 weeks between September and December 1929 on what is now the Universal backlot, probably using left over sets from The Golden Dawn to recreate Neu Posen, a fortified border town separating British and German East Africa, the two competing colonial powers, on the eve of The Great War.

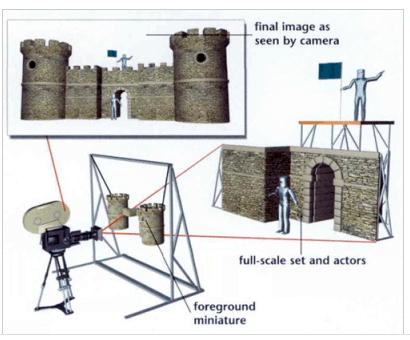

Mamba was shot in approximately 10 weeks between September and December 1929 on what is now the Universal backlot, probably using left over sets from The Golden Dawn to recreate Neu Posen, a fortified border town separating British and German East Africa, the two competing colonial powers, on the eve of The Great War. This wide establishing shot of Neu Posen is an example of a time honored in-camera effect known as the glass shot, where peripheral aspects of the setting are painted on glass which is then positioned in front of camera to blend in with the action visible beyond. Thus, painted jungle obscures the studio buildings adjacent to the set. The foreground lake is still used by Universal for movies and its theme park stunt show.

This wide establishing shot of Neu Posen is an example of a time honored in-camera effect known as the glass shot, where peripheral aspects of the setting are painted on glass which is then positioned in front of camera to blend in with the action visible beyond. Thus, painted jungle obscures the studio buildings adjacent to the set. The foreground lake is still used by Universal for movies and its theme park stunt show.